00:01:04 Himalayan languages origin, overlap and geographical influences

00:11:00 Self-sufficiency, socioeconomic development, education and the impact on languages.

00:17:00 Becoming interested in ‘Monyul’ borderland region

00:22:00 Karmic link in Bhutan

00:28:00 Becoming more a part of these Himalayan communities.

00:43:00 Duhumbi language and culture

00:53:00 Specific kinds of homemade alcohol

00:58:00 Nomadic Kusunda community, language and culture

01:08:00 Connection between health and speaking one’s indigenous language

01:16:00 The future

01:21:00 Learning a language

Kamala and Gyani Maiya, the last Kusunda speakers in 2019, being recorded while commenting on 1968 video recordings of Kusunda people, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2019.

Kamala and Gyani Maiya, the last Kusunda speakers in 2019, being recorded while commenting on 1968 video recordings of Kusunda people, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2019.

Kamala, last remaining speaker of Kusunda, having small talk with the new generation of Kusunda learners, Dharna, Dang, Nepal, 2023.

Kamala, last remaining speaker of Kusunda, having small talk with the new generation of Kusunda learners, Dharna, Dang, Nepal, 2023.

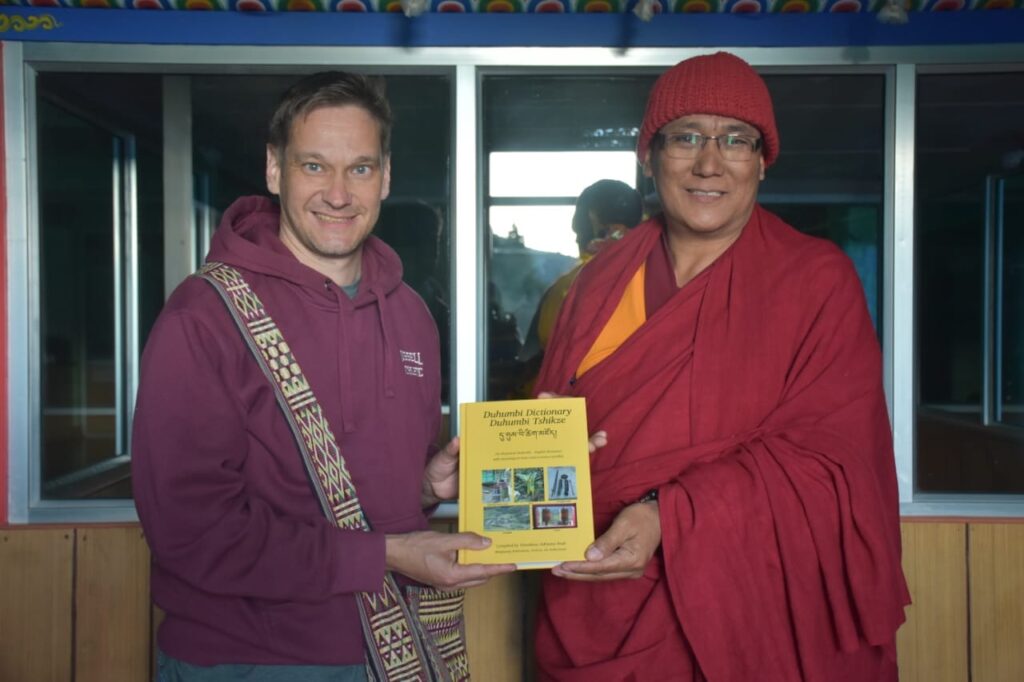

Presenting the dictionary of the Duhumbi language to the librarian of the Upper Monastery in Bomdila, the district headquarter of West Kameng district, Arunachal Pradesh, 2022.

Presenting the dictionary of the Duhumbi language to the librarian of the Upper Monastery in Bomdila, the district headquarter of West Kameng district, Arunachal Pradesh, 2022.

A traditional farewell at the village boundary, with local liquor and soft drinks, Ramjar village, Trashiyangtse district, 2006.

A traditional farewell at the village boundary, with local liquor and soft drinks, Ramjar village, Trashiyangtse district, 2006.

The kosampa dress fabric re-used as bag for transporting grain, then used as rag and finally thrown away to be picked up by a visiting foreigner, Ramjar village, Trashiyangtse district, 2006.

The kosampa dress fabric re-used as bag for transporting grain, then used as rag and finally thrown away to be picked up by a visiting foreigner, Ramjar village, Trashiyangtse district, 2006.

Offering bangchang, ‘beer’ made by soaking fermented grains in hot water, used to be an integral part of receiving guests at home. Offering food would usually follow. Shader hamlet, Duhum village, Chug valley, Dirang circle, West Kameng district, Arunachal Pradesh, 2015.

Offering bangchang, ‘beer’ made by soaking fermented grains in hot water, used to be an integral part of receiving guests at home. Offering food would usually follow. Shader hamlet, Duhum village, Chug valley, Dirang circle, West Kameng district, Arunachal Pradesh, 2015.

Tim relegated to the job of amaranth threshing with a straight stick, after his unsuccessful tried to assist in threshing finger millet with the rotating thresher called yarjung, Tsangpa village, Chug valley, Dirang circle, West Kameng district, Arunachal Pradesh, 2015.

Tim relegated to the job of amaranth threshing with a straight stick, after his unsuccessful tried to assist in threshing finger millet with the rotating thresher called yarjung, Tsangpa village, Chug valley, Dirang circle, West Kameng district, Arunachal Pradesh, 2015.

Witnessing and participating in local festivals is an important way of getting acquainted with the culture and getting people to know you and feel comfortable around you. Choskor festival, Tsangpa village, Chug valley, Dirang circle, West Kameng district, Arunachal Pradesh, 2015.

Witnessing and participating in local festivals is an important way of getting acquainted with the culture and getting people to know you and feel comfortable around you. Choskor festival, Tsangpa village, Chug valley, Dirang circle, West Kameng district, Arunachal Pradesh, 2015.

Links:

Tim Bodt

https://www.soas.ac.uk/about/

https://brill.com/display/

Support the Podcast

Enjoy these episodes? Please leave a review here. Scroll down to Review & Ratings. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/love-liberation/id1393858607

Transcript (please excuse all errors)

Olivia Clementine: I’m Olivia Clementine, and this is Love and Liberation. Today our guest is Tim Bodt. Tim has had a lifelong fascination with the eastern Himalayan region, and in particular with the Bhutan India Tibet borderlands, a region traditionally known as Monyul.

He spent most of the last two decades in various Himalayan countries. He did both his undergraduate and master’s thesis research in Bhutan, followed by a year working for an INGO in Tibet, two years teaching at the then only college in Bhutan, and he spent intermittent periods in Nepal and India. In addition to his native Dutch, Tim is fluent in English and Tshangla, a language spoken in eastern Bhutan and adjacent regions, and is also conversant in Dzongkha, the national language of Bhutan, Tibetan, Nepali, Hindi, Duhumbi and German, in addition to having some basic knowledge of French and Tawang Monpa.

Thank you for taking the time to be here today. And I thought before we go into some specifics about the work you’re doing, you speak many Himalayan languages, and maybe you could speak about the origin of Himalayan languages, and are any of them interconnected?

Tim Bodt: Yeah, thank you very much for having me here . It’s, it’s, it’s my honor to have this talk with you and to be able to talk a little bit about my work. So the Himalayan region is a very huge region, right? It spans basically from, from Baltistan, north of Pakistan in, in the west, all the way till northern Burma and, or Myanmar, as we have to say now, and then southwestern China in the east.

So you can imagine that in this huge region, you’ll also find a very high number of different languages and not just languages, but even language families. So basically all the big language families of, of Asia meet in the Himalayan region. So we have, for example, Austroasiatic languages spoken in a few pockets, languages, which for the rest we find most mostly in Southeast Asia.

We find Thai Kadai languages, like, like Thai itself, or languages of southern China. Then we find Indo European languages, so languages that are basically related to English and to German, to the main, major European languages. National languages like Hindi in, in India or Nepali in Nepal, those are Indo European languages.

So that’s another language family. But the, the largest, most widespread language family of the Himalayan region is basically what has been called traditionally the Sino Tibetan language family, which is also called the Tibeto Burman language family. And more recently my my guruji, my PhD supervisor, Professor Vandarim has kind of rechristened as the trans Himalayan language family, just to indicate that this is a language family which is very much concentrated around the Himalayan region.

So these language families, they have probably connections. The out of Africa theory, once very long time back, these languages came from a single source, but that’s too far away we cannot reconstruct that anymore. But Among these languages, there are basically no genetic relations among the trans Himalayan languages and the Indo European languages, all the, all the similarities that are there are based on contact and then within this, Within this trans Himalayan language family, we have many, many subgroups.

Some languages are very well known, for example, Chinese, Mandarin Chinese Burmese, Tibetan. Those are the written languages. And then we have a lot of languages that are not written, that have just an oral tradition. And those are the languages that you find, for example, in northwestern India, in Nepal, in Sikkim, in Bhutan.

in northeastern India, in northern Myanmar, in southwestern China, and in in, in the Tibet, on the Tibetan plateau. So that’s basically the linguistic picture of the Himalayan region. And then you can focus down, you can basically zoom in on different areas and find that there are different languages represented there and, and a lot of Himalayan languages, trans Himalayan languages, we do not yet know how they are related to each other, even within that language family.

Because they are not read yet properly described, many of them because the ones that are described have not been properly linked to each other, and some because we have not been able to link them up.

And then besides all these big language families, we also have I think probably two, I should say what we call language isolates. One is Burjashki, which is spoken in Pakistan. And the other one is Kusunda, which is spoken in Nepal. So these two languages, basically linguists still now have not been able to.

Say with a lot of confidence that they are related to either the Indo European languages or the Austro Asiatic languages or the Dravidian languages of South India or the Trans Himalayan languages. So these are like language isolates, like we for example also have the Basque language on in, in South, on Western France and on Northern Spain.

So that’s basically the, the picture of Of, of, of the linguistic picture of the Himalayan region. And yeah, you can see it’s, it’s linguistically very diverse. And that’s also reflected in, for example, the biodiversity. Especially as you go from the western side more towards the eastern side of the Himalaya.

As you see there’s different kinds of geographies. There are different kinds of topographies, there are different kinds of climates. So that’s reflected in a very high biodiversity, but it’s also reflected to some extent in, in the high cultural and linguistic diverse diversity.

So that makes it a very interesting region to work in.

Olivia Clementine: And would you say a little bit more, how is that connected the, the landscape and the biodiversity and the language?

Tim Bodt: There are different theories about that. Actually a lot of people say like whether it’s about biodiversity or whether it’s about languages like these all developed in isolation.

So because of the, the, the mountains, the high mountains, you cannot easily cross because of the rivers flowing usually in a north south direction. It’s difficult to cross those. So people settled there and then they developed in isolation species. Landed up there and they developed in isolation and because of many, many millennia of isolation, basically you get this speciation, like that’s Darwinian theory, right?

Like the Galapagos Islands, you get this speciation, different species developing in, in, in isolation in different pockets of the Himalayan region. I think that’s. Perhaps partly true, at least until for, for a certain part of the history, but we can also see that many areas of the Himalayas have actually seen very high population movement.

So people moved, for example, from areas in the plains of India or from the Tibetan plateau, whenever, because those areas, those, those flatland areas are, are easier to conquer, easier to rule. So In the course of history, perhaps people have been pushed out of these the plains of the Brahmaputra or the Ganges, or from the Tibetan plateau, and then found some kind of a refuge there in the Himalayan mountains where they settled among people that already lived there.

They assimilated people, they mixed and that’s how you also get mixture of languages, right? So that might have been another way in which this linguistic diversity can be explained the, the, the level of of migration interaction between different people. And many of these mountains, they’re not unsurpassable.

If you are used to living on the Tibetan plateau and you wear very thick sheepskin clothes, et cetera, and you’re, you’re used to living in this cold climate, then crossing a mountain pass and walking into the Southern Himalayas, for example, is not really a big problem for you. You can manage that, right?

People have been traveling always. So we can imagine that people just. Moved down or moved up and and maybe they even did that on a seasonal basis. Maybe not even a full scale migration, but keeping moving up and down and the same with the rivers. Many of the Himalayan rivers actually in the winter season when the water levels are very are very low.

You can actually just for them at certain places or make a very simple law. Log bridge. You don’t have to construct a huge Right. Bridge which is able to support the truck. You just have to cross people across, right? And, and people have been very inventive. They’ve been making game bridges, for example.

They have, they’ve used logs. They have made different kinds of ways to cross the mountains, to cross the rivers, and to be able to move from one place to the other. And especially in the later history where, where we have some kind of a a record of people population movement. We do find that in a lot of Himalayan communities, they are not, they were not static.

They had people from other places coming in. Maybe if you have a valley, there would be one village that receives one migrant group. Then there’s another village that receives another village that receives another migrant group. And because of that intermix, intermixture of languages, these two villages were, whereas they are actually closely.

together geographically, they develop different languages. So that’s the process that may, may have been going on for many, many millennia. And yeah, it’s this, this mixture that, that might’ve led to this high linguistic diversity in addition to isolation in some areas, probably. So yeah,

Olivia Clementine: From talking to people based in Nepal, it sounds like those routes of migration have changed and maybe like more traditional ways of moving between landscapes based on the seasons has also changed. I imagine you get to witness firsthand the ways that that change in the last 50 years has impacted languages .

Tim Bodt: I think to some extent in the last 50 years it has been a loss of language that is more, more the, more the story in many parts of the world and the Himalayan region is no, no, Nothing different makes no exception in that respect because until 50 years ago, much of the Himalayan region was basically self sustaining, right?

Everyone was just managing their own, their own household, their own village. And yeah, of course there was, there was trade, there was migration, there were religious contacts, there were marital contacts between different populations, but by and large, people just managed their own small village units.

And yeah, that’s just a fact. And, and languages were maintained, but you can see that especially since, since the Second World War there’s been a lot of socio economic development in many of these areas, in some areas a bit earlier, in other areas a bit later, like Bhutan was started a bit later than the rest.

So you can see that With this socioeconomic development, with the arrival of roads, with the arrival of electricity, with the arrival of schools, with the arrival of health units, population increases, but also people get to know more about what else there is in the world and there’s this a little bit of everything.

This, this rural urban migration, for example, where villages become empty because people move to the cities because that’s where that’s where jobs are, that’s where they can make money and these kind of developments, they actually Can be quite detrimental to the to the future of, of small languages because the people that that speak these languages, I found very often that people have an attitude that in order to, for their children to make it in life and to make it in the world, they need to speak the dominant language.

or the dominant languages, whether that is a national language or a regional language. Parents feel that teaching their children their mother tongue might not have a lot of benefit for the children because it will not help them in their education. It will not help them in their career. They won’t get a job because they just, if they just speak their mother tongue.

So they find that, okay, we have, we have to make sure that they know the dominant language. And that is what is going to. advance them and make them have better future prospects than we had when we were their age. So that’s a very valid thought, right? In many ways it’s understandable. But what people tend to forget is that children’s brains are still very flexible.

So children can easily learn. two languages, or three languages, or four languages. They’ll not have a problem with that. And the national language, the dominant language, the regional language, they will by any means learn it in school, through the formal education system. They’ll learn it when they go to the city, because They will be speaking the more dominant language there, they’ll be learning it when they’re playing with their friends from other linguistic backgrounds.

So, the national language, the dominant language, is not the threatened one. It’s the mother tongue that’s the threatened one. And that is what actually should be encouraged to be spoken. At least within the household, so that parents speak their mother tongue to their children, so that the children grow up actually knowing the mother tongue.

And in the last 20 years perhaps there has been this development of social media for the internet television. Before there was just like small radios in villages where everyone would be around the radio. Then came the television, people sitting around one or two televisions in the village.

Now it is everyone having their own mobile phone and checking their social media accounts. And there they also very often use the dominant language. Or even English, because that’s just easier, right, rather than the mother tongue. So you see that, that, that that to, in order to, to preserve indigenous languages there is a very big responsibility for parents at home.

And for many… Indigenous communities and mother tongue speakers. That is still a little bit, a mental change that they have to switch. Like, okay, we’ll just speak our own language at home. For sure. The children will learn any other language in school through social media, through the television, whatever, when they go out, out of the home.

So let’s just speak it at home and make sure that in that way, we, we. We make sure that it doesn’t become extinct. So I think in the past 50 years there have been languages that have disappeared, also in the Himalayan region. And some of these developments may have been just a slow, gradual, natural process.

Some of these languages becoming extinct. has probably been exacerbated by the whole socioeconomic development process and, and education and, and rural urban migration that suddenly money became more important, whereas before people were self sufficient or trading bartering things with neighboring groups, et cetera suddenly there was a need for money.

And in many villages, that is now still the case. Like, yeah, we can manage ourselves, we can feed ourselves, but we have to send our children to school, we have to pay school fees, we have to travel to the hospital, we have to be able to pay for the bus fare. So we need money, we can no longer do without money.

And to get money, yeah. I think It’s difficult to, to, to survive just on purely self sufficient agriculture. So there has to be someone in the family with a job, etc. So yeah, that’s, those are threats to, to, to the survival of many indigenous languages, I

guess.

Olivia Clementine: And I want to go back to extinction later and some of the impact of it that you’ve seen, but also just talking about the fact that you’ve spent a lot of time in communities in this Monyul region. So I have a kind of two part question. One is why this region like why is this borderland region a place you’ve really focused most of your life thus far in in understanding these languages in this area?

And then to how have you been able to immerse yourself in these communities? what do you do to really get to know them and understand all the things you’re sharing right now, right, like what they’re dealing with kind of crossing between historical ways and then modern ways of, of being.

Tim Bodt: Yeah. So this Monyul region,

maybe as a, as a background, that’s like the border area between Eastern Bhutan, South Part of southern Tibet and then western Pradesh is one of the states of India.

So there, this is, this is the border area, it’s known as the Monul region. It’s, that’s a Tibetan name. And it’s, it’s a very old region, very historical region. It, it, it’s attested in several Tibetan documents of a long time ago. Some Bhutanese documents of the 17th century make mention of it.

But not much is known for the rest because there’s just a lack of. written sources and there hasn’t been so much archaeological research yet. So maybe that makes it interesting, right? Just the, the, the fact that so little is known about it, that, that makes you curious, like what’s been going on there.

And it, my, my interest in, in, in the region basically Started when I was, when I was in my teens with a kind of a fascination for the Himalayan region in general and with Tibet and with Bhutan and through, that was pre, pre internet. So. Mind you, I had to like go to the library, physically go browse through books and write letters to people in Bhutan or in, in Europe, like, Oh, I’m interested to know more about this.

And this I saw in the newspaper article that you have been there. So would you please tell me more like that kind of, it was still very, how do you say primitive? Maybe in a sense I was not going online and then. Going to Wikipedia and, oh, Bhutan. Let me see what’s written about Bhutan. That’s, it’s become much more convenient these days than, than in those days.

But it was also very adventurous, I guess, to, to find out in that way. So I was making contact with people in Bhutan, making contact with people who were working. In Bhutan, European people, Dutch people. And then I met my later PhD supervisor, Dr. George van Driem who has also, who had also worked in Bhutan, who was working in Bhutan at the time.

Then I was introduced to Bhutanese people, the few Bhutanese people who were in Holland, like a few of them were working there not actually working, studying, most of them. And a few of them had married there. So, yeah, that’s how I rolled into that, that connection. And then I went to Bhutan and 2000 for my master’s thesis work.

And from there it just started developing. And when you’re in Bhutan and you hear about the region to the east of Bhutan, where people are very similar but still very different, then you think like, oh, that also sounds very interesting. So, you know, it’s just this curiosity that you feel like, okay, I would like to know more.

And and finally, Many years later since my first, many years after the first visit to Bhutan, I, I went to Arunachal and then mainly for my PhD research from 2012 to 2017. But yeah, that, that, that is how this interest basically grew. For Bhutanese, there’s another thing that plays a role.

The first, probably the first newspaper article that was published about me in Bhutan said was entitled a Bhutanese born in the wrong country. So for, for many Bhutanese, the fact that I picked up their language very easily and I managed to get along with them very easily and and that I, I, I was able to to teach myself reading and writing the Tibetan script, Dzongkha, and the interest, the interest in itself, it, for them, it was kind of, oh, there must be some karmic link, like, maybe in one of your previous lives, maybe not the last one, but some of the, like, a few lives before you have been a Buddhist, it must have been otherwise, this kind of an interest and this kind of a aptitude also would not come.

Naturally, if you were like just 100% from Europe, so for them, that that that has always been a little bit it’s difficult to kind of say whether that’s right or not. Usually When children are small and they speak in different languages or they have different reminiscences of their previous lives, then it’s easier to find out, okay, it must have been from this or that place, this or that family sometimes even.

But yeah, when you, when you’re already in your teens, then that’s more difficult to figure out. Right. But when, when I was in Bhutan, I also remember I, I, I was like adopted by a Bhutanese family from Ramjar in Tashianti in the eastern part of the country and I visited there and then I went to visit one old Lama, like a Not an ordained Lama, but a local village Lama named Wangpo in Kalapangthang.

He was like on top of a hill. And from the main village, you had to walk for one and a half or two hours up to, to his place. And he was living there with his wife. And I think I remember correctly his daughter. And we were just sitting there and talking. And then when I was leaving, I picked up a old…

Rag. So it was a a tonku, like which they used to store grains and I picked it up and I said, oh, this is nice. Can I take that? And then they said, well, we threw it away. It’s a rag. We don’t do anything with it anymore. Take it if you want. And then when I came down to the village, they were saying, like, where did you pick this up?

Where did you find it? And then the relatives down in the village said, like, this is actually a Yeah. piece made from a piece of cloth which belonged to our late father, his dress. So in, in the olden days in Eastern Bhutan, people used to grow their own cotton and then they used to dye, dye it in basically just two colors.

It was either white or they would make it like a bluish black, or it used to be a kind of a red red color. And then they used to weave their own clothes. And for men, it usually was. But then to make it a little bit special, they would sometimes weave in very thin black and red lines. And that’s called like a, the national dress in Bhutan is called a go.

In Eastern Bhutanese it’s called chupa. And this kind of chupa, the pure white one, it was called kamthama chupa. Then if they make it with the three lines, alternating lines, it was a Kosampa, like a three doors. And if it was with five lines, it would be a Kongapa, so five doors. So this was a Kosampa. So they were saying like, ah, this is actually this, this bag that you picked up, this rag, it actually, it, it is made, it was made from the Kosampa.

Chupa dress that belonged to our late father. So for them, that was also like, okay, there must be some connection. You don’t pick up a rag like that just, just because you see it. So there’s always this kind of small, small things that people have been saying like, okay, there must be something more than just an interest.

There must be something more than than just curiosity. So and yeah. It’s still a very interesting area. And the, the sad thing to an extent is that it’s not very easily accessible, especially the part of Monyul that’s now in, in China. It, it’s, it’s not accessible for, especially for, for foreigners.

So I’ve been to Tibet, Arunachal, it was.

Quite difficult before, but now it’s not that problematic anymore in Bhutan yeah, as a tourist to go there as a tourist is of course a bit expensive, but it’s still possible to go there. So yeah, that, that the fact that this, this area, it became divided in three different countries.

Basically during the 17th century and then of course again in the, in the second half of the 20th century. But you can, you can notice that people from different side of the border still have a very good recollection that actually they are very closely related to each other. The Chinese part is the Tibetan part is now a bit cut off but for between Arunachal and Bhutan, there are still a lot of relations and those relations are actually improving.

Also because of the internet people get to know more about people on the other side of the border again, whereas it was kind of disconnected for some time. And yeah, I’ve always enjoyed very much the people there as well in that whole area. I mean, in general, Tibetans, Bhutanese, Nepalese people from Arunachal, Sikkim, they’re very…

Amicable people, hospitable people friendly people, they always enjoy good love. They always invite you to come and eat. So yeah, that’s that’s the same in the Monyul region as well. People are very, very kind, just very sociable. And and, and that’s also very attracting me a lot to that region.

And to become part of a community, I think it’s maybe It would be the same if you’re, if you’re a born and bred Londoner and you move to somewhere in the Surrey Hills of outstanding natural beauty or somewhere in the in the Lake District in a village or something like, you will always kind of remain an outsider, right?

You cannot become 100% part of another community unless… You really start living there and live there until the day that you die, but if you’re there for, for, for a shorter period you can do your best to to, to, in your daily life to become a part of the community, I don’t think you can really assimilate into the community but I think both the person moving there and the person and the community itself, they need to be open for such a relationship.

And I can give the example of during my PhD when I started my first started my PhD, I was actually thinking to work on the Lish language. Khispi, as they know it themselves, Kispimak, so that’s also spoken in Arunachal Pradesh. And I had a few friends from the district capital Bomdila and from the circle capital Dirang and they took me along and and they introduced me to people there.

But the reception was a little bit I would, I wouldn’t say hostile, not at all, but a little bit People were a little bit wary, like what is this foreigner coming to do here? Why does he want to stay here in our village? Why does he want to make recordings of us? Why does he want to write about our language?

What’s in it for us? What are we going to get from this? So you try to explain to people, but if you notice that people are not really that much forthcoming, then you think like, okay, maybe I should try something else. Maybe we could make it work, but it would take a long time. So that’s when, when actually my, my friends from the area who introduced me, and that’s also very important, especially if you’re, if you talk about a rural community, that people there should be people who properly introduce you, especially if you are a foreigner, especially if you are an outsider.

So they took me to the, to the Chug Valley, which is, Basically 20 minutes, half an hour drive from Lish Village and there the reception was completely different. So there was a circle officer, the only person from the Chug Valley who had a government job at the time. He was there constructing his house and I talked to him.

And he was saying, like, oh, this is very interesting. If you want to write about our language, if you want to write about our history, about our daily lives, you should do that, because no one has done it before. And, and someone should record this for, for posterity. So please go ahead. And why don’t you go and meet my sister, who is up there doing something?

Why don’t you go and meet her and her husband and explain to them, and they will be very happy to help you. And. I went there and within, I think, One hour I got absorbed into that family, taken to the family home, and and met everyone in the household, met everyone in the extended family, got introduced to the village, got introduced to the whole valley.

So they were, they were much more receptive and they said, yeah, of course, we really appreciate if you’d like to write about our language and write about our history and and, and, and be here and be welcome and have something to eat, have something to drink. So, yeah, it was a, it was a different reception and, and that shows clearly that some communities have a different, but it’s also individuals, of course, right?

Maybe I just, in this village, I just, met the wrong individuals from the outset, whereas in Tchouk I was introduced to the right individuals from the outset. And once you have that, once you have that entrance, once people are, local people accept you and explain to other people in the community about you, then it becomes much easier for everyone to, to, to, to accept you and, and, and understand the work that you’re doing.

And yeah, then, then it becomes a process of it takes time. And I think that’s, that’s, that’s what lacks for many people, people who do their PhDs, for example. You are on a very shoestring budget. Usually you don’t have much time to spend in the field. There may also be a lot of practical problems, for example, infrastructure or electricity problems, etc.

But I think that it’s very important to spend as much time as you can in the community itself, especially if you’re doing ethnographic, anthropological, linguistic fieldwork. Where you really have to connect to the people and make sure that they they open up to you and they share with you. And that takes time.

And I think maybe like two, three months or something continuous for a visit that, that would be kind of. the minimum in order to be able to actually meet people properly, be introduced to people, get to know them, but also throughout a whole year, even if it’s not continuous, to see the different seasons, to see what people do in different times of the year, which agricultural activities they do in summer, what they do in winter, which festivals they celebrate in different times of the year.

So yeah, it takes time. That’s the second thing. You can’t expect to do something like that in just two or three weeks. Go in, make your recordings, go out again, and that’s it. Yeah, maybe for some purposes it would be sufficient, but if you really want to get to know the people and get to understand them and what drives them and also know more about the language and the culture, then you Yes.

Spend a longer time. What I think also is very important is that that you have to understand people’s personal lives. And that also means. Not be too intrusive in a sense, and that’s what I often found very difficult that people are very kind, almost too kind in the sense that they want to make sure that you are pleased and happy and be able to do what you aspire to do 100% of the time.

And sometimes people, for example, the lady that, that, that took me into the house in Chug, in the Chug Valley. She’s also the mother, she was, she still is, the mother of four children she’s married, she has a husband, she had her in laws, elderly couple living with her, she was a farmer, full time farmer, so she has to do all the agricultural work she was the Anganwadi, like the local women’s self help group, she was kind of a midwife, and because she has she was a little bit well, reasonably literate, and she could read and write both Hindi and, and, and some English.

She was always the one to go to the nearby Circle headquarters to do things for people, apply for government subsidies, fundings bank, open bank accounts and whatever. So she was very, very busy. And, yeah. She was excellent as a language consultant, she was excellent in helping me, in helping me understand their language, in introducing me to people, in giving me the ins and outs of village life, etc.

But, Sometimes I had to make sure that I was not demanding too much of her time and not intruding too much into her family life, her personal life by constantly asking, Oh, I need you to come and sit with me and look at this. Text, translation, transcription, I can’t figure it out, I need your help. So that’s sometimes very difficult.

They want to please you, they want to make sure that you get your work done. You also want that, but you have to understand like, okay, they also have their own lives. So let’s, let’s give them their space and let’s just do it myself. Sometimes you, yeah, it’s good to just move out for some time and let people do their thing.

Sometimes it’s good to just. Go and sit somewhere where no one is there to disturb you, but also where you can create the feeling that people have to help you at that moment. And yeah, it’s, it’s good to adapt to what people actually do. So. If they go to transplant the rice, the paddy seedlings, then just go and help them, which is a terrible job in the Chug Valley because the, the, the, the, the layer of mud there is incredible.

Like I sunk until my thighs. So you can imagine that someone who reaches to my basically to my not even shoulder would sink till basically till their mid, mid rib. Into the mud when you’re transplanting rice seedlings. So it’s, it’s and it was raining and it was cold and it wasn’t in summer, but because of the rain, it became very cold.

And it’s, it’s it’s interesting, but I think I lasted less than a day. And the same thing also with for example, threshing paddy they use sticks. And I think maybe I’m too tall, I haven’t been able to figure out exactly why it was so difficult for me, or maybe just because of the bending. It was, it was very difficult for me to do that.

Like threshing finger millet with a rotating thresher, that was also impossible. Finally, after they saw me struggle, they were like, okay, you just take the stick and start threshing the amaranth, which is also kind of a millet species. So just trash that. You’ll be okay with that because what you’re doing right now, it looks so awkward.

So we don’t want you to end up with a, with a terrible back pain. But yeah, it’s always nice to, to participate and to to try things and to, to kind of do what they usually do, participate in their local festivals. Yeah, just that’s also how you learn about the culture. And if you’re describing things, then that is that is the way to, to, to know what’s going on.

And it’s, it’s good to, to learn a language, of course. In the end in the beginning, it’s usually very difficult to first get a grip of a new language, but again, if you stay there long enough and you give yourself time and you’re, you’re you’re open to it, you’re willing to learn, you’re willing to make mistakes.

And willing to learn from them, then I think anyone can, can learn another language, right? So even in, in, in a village where, A language has never been described before, and there’s no book from which you can learn it. You could still try to learn it from the people itself. And I always found it very useful, for example, to speak to elderly people, who did not know any other language that I knew.

So in the village, there may be people who don’t speak any English, any Hindi, any Nepali, any Tibetan. Of course, I had the advantage that the people there speak Tshangla, the Eastern Bhutanese language. So even in Arunachal Pradesh, it’s, it’s it used to be kind of a lingua franca in that Dirang area.

So I could, I could start with speaking in, in Tshangla. But elderly people and small children are always a good way to learn the language because they They usually don’t have that much knowledge of other languages. So to learn from them is yeah, is, is is a very effective way in learning a language to try and communicate with them and talk about just anything like daily life.

What are you doing now? Where are you going? What are you eating? Yeah, I think that, that those things like that, you should spend enough time there. You should be willing to to, to, to learn the language and to participate in people’s daily lives. I think those are very important if you want to try and and, and maybe not become.

Become a part of the, maybe a temporal, like a for, for some duration of time to become part of, of the community. And, you will, you will definitely notice when people have kind of accepted you, they’ll be inviting you over, they’ll be telling you, asking you like, please, can you help us with, with threshing the paddy tomorrow?

They will just, they’ll just. They’ll just behave in the way that, that, that they think, okay, he’s not here, just the person, that person is not here just for temporary, just to do his or her job. They’re actually here to, to learn more about us and about our, our, our culture and, and our language and to try to become part of us, even if it’s for a limited period of time.

Olivia Clementine: And will you share about. These two languages, the Duhumbi and Kusunda language that you’ve spent a lot of time learning about. Maybe we start with Duhumbi.

Tim Bodt: Duhumbi was what I worked my PhD on for four or five years, probably, little bit more, I guess. Writing a grammatical description in a three year PhD is basically an impossible job. I don’t, I don’t know many people who manage that.

Usually it takes at least two years longer, I guess to come to the complete grammatical description. So it’s spoken in, in, in Arunachal Pradesh, which is the northeastern state of India, bordering on Tibet, Myanmar, and Bhutan, and Assam in the south. And Duhumbi is spoken in the Chug Valley which is not very far from either the Tibetan nor the Bhutanese border.

So it’s it’s in a valley. There is three main villages. Then there are a few hamlets, and it’s around, spoken by around 600 people. So that’s, it’s not a big language, it’s not spoken by many people. And like I said before, the people of Lish village they speak. a very closely related language.

They’re a bit more of this Lispa. So they are trans Himalayan languages. They belong to the same language family as Tibetan, Chinese, Burmese, and To the outsiders, they call themselves the Gumbi, the people of Duhum. So for them, Duhum is the name of the valley and the main village. To outsiders, they’re known as Chupa and Chuk.

The Tibetan Chuk can refer both to wealth and to cattle. So I, I guess they got that name, they were given that name by Tibetan administrators or someone because of it’s a very, I wouldn’t say rich, because then you get associations with rich in monetary terms, but probably like a wealthy, a wealthy valley in the sense that it’s very fertile.

It has a lot of good soil, which can support a lot of different crops. They have paddy, they have maize, they have different species of millets, various kinds of vegetables, they have forest nearby, and they can collect any mushrooms, berries green leaves fruits, whatever, from the forest. Firewood is there.

And they have a lot of, they used to have, and they still have, a lot of cattle. So cows and cow and the local -, it’s called. It’s a typical northeast Indian breed of cattle. So crossbreeds between those. And I guess that’s where the name came from, that connection between cattle and wealth.

That’s very strongly part of Himalayan culture to different parts of the Himalayas, including the Tibetan plateau. So that’s, that’s a bit of background about, about the Chug Valley. You, you should, you haven’t been there, right? You should visit it if you have the opportunity. It’s very beautiful.

Just, I don’t want to advertise it too much, but… And, and their language, like I said, it’s related to… To Lispa, to Kispi, which is spoken maybe 1, 500 people in Lish village and some hamlets around that. It’s also related to Sardang, which is spoken more towards the east in four, four villages. And it’s related to Sherdupen, which is spoken in two villages to the south.

So we know these languages group together. Then there is a language called Bugun, a language called Puroik, on which my colleague Ismael – wrote a grammatical description. So probably these languages are also, to some extent, at least related. But beyond that, we don’t really know. Where they really fit in, in the whole language family, we do not have much idea yet.

Of course, there are a lot of theories about it, and there have been some proposals, but It’s not, not yet. The evidence is still awaiting discovery, I guess. And yeah, Duhumbi has a basic subject, object, verb, word order. So if I ask you now, that means like, are you okay? Nang is you. Uhang means Well, or good, but of people or animals, and then B is like, it’s a copula, like the equivalent of English is, is, are, to be, the verb to be, and then N is a question marker.

So, Namuhangbeini means are you, are you okay? And they don’t really have a word for hello, which is also not very uncommon in the region. A lot of people, they don’t really have a word for hello. If you meet someone in the Chug Valley, then the question would usually be Where are you going?

And if someone is, is clearly moving away from the village, then the question would be, Nam Hako Aba? What if people, if someone is moving towards the village, then it would be like, Nam Halolonda? Where did you come from? Because home is the village, right? So, if you move away from your village, That means that you’re going somewhere.

So where are you going? If you’re moving towards the village, you’re going home. So where have you been? Where are you coming from? So that is the basic hello. Or if, if, if someone is not moving somewhere, someone is sitting somewhere doing something. Even though you can see what that person is doing, like maybe tying his shoelace, or cooking food, whatever, you’d ask, Nang able daya?

What are you doing? Even though it’s completely obvious, Nang able daya? What are you doing? So that’s like that’s like the kind of, hello? Just these kind of simple questions. And people would say like, okay, I’m tying my shoelace or I’m cooking food. And if someone is like just sitting around with people, which people also like doing, then they might say like and just sitting around like this.

Without any real purpose or intent, just sitting here and being myself. So that would also be a possible answer. And if you enter a house, then people people may ask you Did you eat food? That would be a very common question if you enter a house. And if you, if you would say, Bang, I haven’t eaten yet, then the invitation would often be like, okay, Mo, Chanyu, let’s eat.

So people will invite you to join them for food. And that’s, that’s very common to, to be invited for food, to be invited for drinks. Yeah, they’re very hospitable, like I said before, and, and eating and drinking together is a very important part of people’s people’s social of the culture, etc.

So they will invite you very easily, they’ll invite you in, they’ll invite you to join them for dinner, even if they may feel a little bit shy about what they’re serving you, because especially for outsiders, They, they, they eat a dish called shajo or gripchura, like it’s fermented soybeans which is quite common in different parts of the Himalayas.

For example, you’ll find it in Eastern Nepal, where it’s called kinema in the Kiranti areas. You’ll find it, I saw the name today, but I forgot again, in, in the Naga areas of Nagaland. And, and adjacent areas, you also find it. And then in, in Western Arunachal and previously also in Eastern Bhutan, but there it has kind of been replaced by cheese.

So what in Bhutan is the common emadatsi, like chili with cheese, in, in Arunachal Pradesh, they would make that with the fermented soybean. So it’s like basic, basic condiment that, that everyone uses when they’re. cooking food. It’s even in Arunachal now in many areas, especially the younger generation, they don’t like it as much anymore.

They don’t, they prefer to fry things in the, in the Indian way with masalas with different spices. So the food culture is changing quite rapidly, but in the villages, you will still find this fermented soybean and For many people, I guess it’s an acquired taste. So not everyone would appreciate it. Same as with the local liquor as well.

People used to drink a lot of banchan, which are basically fermented grains, which can be any grains. Usually it’s a mixture of a finger millet, maize and different kinds of other kinds of millets, whatever is available. Sometimes also rice. They’ll ferment that and then pour hot water and then squeeze out the liquid, the resulting liquid and drink that kind of a beer.

It’s quite light. It can also be distilled in, in which it becomes Ara, which is can be quite strong depending on the hand of the lady who has distilled it. But yeah, that that’s also an important part of culture drinking alcohol. People used to drink a lot of alcohol. I remember even in Eastern Bhutan, even in Arunachal Pradesh from morning till evening especially people who are working on the land because they need the energy.

So they would start the morning with alcohol and basically throughout the day they would have breaks in the agricultural work and they would drink a little bit more again. Now of course that, that has kind of changed. Maybe not necessarily that people drink less, but the, the, the, for example, that those fermented grains that is now Very, very rare, becoming very rare people drink either the distilled one, the Ara, or they buy beer and whiskey, rum, et cetera, from outside.

So, maybe the amount of alcohol being drunk is not necessarily less than it was before. But the, there has been a shift in, in the kind of alcohol. And that’s kind of a pity because of course the, the local food grains, they grow themselves. The way of preparation, et cetera, without chemicals, without any additives.

It’s much purer and especially the Bang Chang, it’s quite light. So it doesn’t have the same effect. It still contains a lot of energy so people could do their work. Now with all these cheap. Cheap whiskeys and rums. I think it’s maybe a little bit more dangerous for people’s health, but yeah.

Olivia Clementine: I also noticed some of the alcohols had egg in them, like they, what, I don’t know what, which one that is, but they’d mix egg with the grain. And I thought to myself, oh, that seems really thoughtful. In Bhutan, at least the alcohol that was homemade they’d add egg in it and I thought, oh yeah, that’s good for sustaining one’s energy over, over time.

Tim Bodt: Yeah, yeah, it’s very common and, and it can be anything egg is, I think. It is also kind of kind of respect towards a guest that you add something to the alcohol that you serve.

So first of all, it’s usually warm and then it’s, it’s heated in, in butter. And then they add something. So I, I’ve seen different things. I’ve seen egg, very common, especially in Bhutan, but sometimes eggs are not available. Small pieces of dried meat. I’ve had those in the, in the, in the Ara, in the local warm local drink.

I have had Karang, no, not Karang, Ashantanga, which is like, pound maize. So kind of cornflakes, basically cornflakes in it. I’ve also had hornets larvae in it. So that, that is really like very rare. It’s kind of a speciality. It’s supposed to be very good for health. Like some health benefits are there.

So they go and they, they dig out the underground nest of the, of the hornet, and they take the larvae, they dry them, and then to be served that in, in the local liquor, the warm local liquor, that’s really like, okay, this is, this is for very special occasions. But yeah, so it’s, it’s, I think it’s kind of a respectful thing to not serve this White liquor, just in, just like, just like people would not really serve plain water.

A glass of water, if you ask for a glass of water, they’re like, no, we’ll make tea for you. No, I just want water. Ah, it doesn’t, it’s no problem. Within a few minutes I can make tea. And then it will be tea with milk, tea, and there will be milk, there will be sugar, there will be tea leaves, and there will be water.

If you say like, no, I will just have a black tea. No sugar, no milk, no camoon. We have milk, we have sugar. So it’s kind of, the kind of respect that, that, that guests are being that be, that they, that they give to guests, that, that it should be a little bit elaborate, whatever you serve to a guest. And, and just as, just a small cup of plain white.

liquor is maybe too common in a sense. So to make it a bit special, there’s butter, there’s egg, and yeah. Maybe

Olivia Clementine: if you’re lucky, hornets larva. If you’re really lucky.

Tim Bodt: If you’re really lucky. Of course for vegetarians that would not be.

Olivia Clementine: Yeah, yeah. And then so now you’ve been really immersed in the Kusunda language and Kusunda culture.

I know you’re doing further research on that right now. Would you want to share about that community, where it’s located?

Tim Bodt: So, so Kusunda is, it’s outside of this Monyul area.

It’s far to the west, in central and western Nepal. Western Nepal, technically, I think. Yes, western Nepal. So the Kusunda, They are a very small group of people. They are now 161 people that ethnically identify as Kusunda. They live spread over maybe six, eight, 10 different districts of western Nepal.

Usually there are just like one or two Kusunda households in one village. So they’re very scattered over a very wide geographical area. And there is just one person left who speaks the Kusunda language. So Kamala. She is she’s in her 50s. She is the last person to speak the Kusunda language.

It has been, I guess, a very gradual decline. The Kusunda used to be a nomadic hunter gatherer community. They used to be marrying only within their own group, their own Kusunda group, so endogamous, but then within this Kusunda, they had different clans, and people from the same clan could not marry each other, so they had to find spouses from the other clan, and then they were traveling around the forests, the middle hills of, of western Nepal living in living in a place for a couple of days, maybe a week at most, sleeping in caves.

They would construct lean to’s like small houses of branches covered with leaves to sleep in during the night. And they would basically live off the forest. So the men would go hunting with bow and arrow. They would. only eat animals that live and roost in trees. So that means, for example, squirrels or pheasants or birds or civet cats.

So anything that would, that would roost in a tree, they would not. Hunt or not for their own consumption, at least they would not hunt barking deer or wild goats or wild boar or whatever. So they, they had a taboo for other kinds of animals that did not live in trees. And they would not rear any domestic animals.

They did not have. Any, any cows or pigs or whatever, because they were moving in the forest. So it will be difficult to, to, to take care of those. They would not practice agriculture and they would basically dig up different kinds of roots and tubers in the forest, collect berries, collect mushrooms, different kinds of leaf vegetables, fruits whatever they could find edible things they could find, they would survive on those things.

And they maintain that, that, that lifestyle. probably until the mid 19th century, maybe a little bit later in some cases but yeah, as there were different groups migrating from other parts like Indo Aryan speakers coming from, ultimately from northern India, entering Nepal from the west maybe before that already trans Himalayan speakers coming from somewhere in the east, we don’t know yet where people came from, but more and more people settled in, in the same areas in, in western Nepal started agriculture, making villages burning the forest, for example, for regrowth of grasses for their cattle.

So yeah, slowly that the, the forest where these Kusunda were living was decreasing and And, and it became more and more difficult for them to maintain that nomadic lifestyle. And it also became more and more difficult for them to meet people, Kusumda people of another clan to get married to, for example.

So especially, I think it’s a process which had been going on for, for at least a millennium and several hundreds of years, at least. But it was really, it really, it was The process of the Kusunda settling in villages was Really becoming much faster in the, in the probably the mid 19th century right into the 20th century where more and more Kusumda decided to get married to people of other ethnic groups, or even people of higher caste in Nepal and live in the villages.

So, one by one, these, these nomadic Kusunda groups, they fell apart, and people settled in different villages, and that’s why you can find the Kusunda households now in, in, in such a scattered scattered pattern in different districts of, of Nepal. So, slowly but steadily this, this Kusunda, they married outside their own…

Group, they married in different, different places, not in the same village. So they had to speak to their spouses and their in laws in another language. The village surrounding them, the community was speaking in another language, maybe sometimes Magar, sometimes Gurung, most commonly Nepali. So that’s how slowly they gave up their own language.

And And that’s how we ended up with, in 2019, just two speakers left Gyani Maiya

and

Tim Bodt: Kamala. And then the eldest speaker, she passed away early 2020. And that’s when we were left with only one speaker of Kusunda, at least to our knowledge, and I think my research counterpart in Nepal, Uday Raj Ali, he has a very good overview of the Kusunda people in Nepal.

So I think we can, with a fair amount of certainty, say that there is no one else left who, who speaks the language anymore. And Yeah, that’s, it’s a pity. Also from a scientific perspective, because like I said in the introduction, Kusunda is considered a language isolate, like Basque, like Borusheski, we have no idea to which languages it’s related to.

There have been some proposals, but the scientific evidence, the hard facts are still missing. So yeah, from a scientific perspective, of course, it’s very it’s a very interesting language. But also for the Kusunda people themselves, the loss of their language is, is it’s a sad thing. And it’s, it’s, it just happened in the course of hundreds of years, slowly, maybe in a little bit.

Advanced at a little bit advanced speed speed in the in the last 100 years or something. But yeah, now there’s just a single speaker left. Luckily, the Nepal government, the Nepal Language Commission has been supporting – to teach the language again. So he has written textbooks. He has been teaching the language for the past four years together with Kamala with a little break in between because of the pandemic.

And now there are Some young Kusunda people who can manage to speak their language again to a reasonable extent. So maybe they’re not yet completely fluent, but at least they can manage small conversations. They know the words, they know the verbs. So it’s, it’s a process of revitalization of the language that’s currently ongoing.

This, this was actually possible because The Nepal government supported I think there were 12 of them, 12 Kusunda students, because they were, they are considered a disadvantaged group, to study in a boarding school together. So there was this group of Kusunda, young Kusunda people, students, who could be taught a language.

Because otherwise, because of their scattered residents, it’s very difficult to organize revitalization classes if people are staying in all these different places, right? So for the adult classes, it was also a bit difficult because people were interested to join, but then they were living 200 kilometers away or 150 kilometers away up in the mountains, down in the valleys.

So yeah, it was difficult to, to attend such kind of revitalization. Classes for many people and, and that’s still a little bit the limiting factor that, that people, the Kusuna people live so scattered. And of course, other things are, are a lack of funding and the lack of manpower because basically Uday and Kamala and then One younger Kusunda lady, Urmila, they have been the ones that have been doing all the teaching for four years.

And but things are happening. And for the Kusunda themselves, it’s very important that, that they have the idea that, that something is being done to not only document and describe their language, but also to try and promote it again, to revitalize it again.

Olivia Clementine: And can you speak about some of the benefits you’ve seen of a community Being connected to their indigenous language.

Maybe I read someplace that you’d seen some patterns between the health of the community and their connection to their mother tongue.

Tim Bodt: So Our whole world is basically reflected in our language, right? Because through language even if it’s sign language to any kind of language we communicate with the people around us and everything that.

is inside our mind, inside our head. The way in which we share it with other people, unless you’re telepathic, which I think not many people are, the way in which you share your thoughts, your feelings, your impressions, your view of the surrounding world, it is all done through language. And this language Encapsulates your whole worldview and the worldview, not only of individuals, but of households of families of villages of communities.

So in that way, it’s, it’s really important for many communities, especially indigenous communities to have their language because it, it’s not just the worldview of that community at present, but the collective knowledge of all these generations that were before them, and for example, the Kusunda people, they were saying like before we used to live in the forest, we were nomads, we used to hunt and we used to gather from the forest.

We no longer do that. For the past 50 years, 60 years, all Kusunda have been living in villages and have been rearing cattle, milking cows. Before they didn’t even used to drink milk or touch cow dung. Now they’re rearing cows, they’re rearing buffaloes, goats. They are growing maize, different crops.

So their culture has very much changed. They speak they sing Nepali songs, they wear Nepali dress. They’re, they’re basically become like, many other people in Nepal. And the only thing that still connected them to their past was the language in which you could express things like, oh ui means lean to, in which we used to live.

And this Yirgamba means the the, the, the civet cat that we used to, to hunt. So all these things were still connected with the, the knowledge was still there because it was preserved in the language, but when the language disappears, then also that whole that whole knowledge of the past, of their past lifestyle, of their past culture, that, that also.

That also is no longer accessible. So from, from these perspectives, it’s a very important part of identity, of the identity of indigenous people. Their language is a, is a very important part. It’s not the only part, but the Kusunda example shows that when everything else is gone, when the dress is gone, when the songs are gone, when the lifestyle is gone, then the language is still considered as that last remaining link to…

their original culture, their original identity, their original lifestyle, or their history, whatever was there before. And that’s why they also find it so important to reconnect to their language and for the language to, to be revitalized again. And Kamala the last speaker of Kusunda, she expressed it like,

Which means something like, okay when rope of our life, Is cut like our life, our soul is cut and we die. And similarly, when the rope, when the soul of our language is cut, we die. So where did our language go? And that’s another thing that they never speak about our language has died.

Or we, our language is moribund or our language will become extinct. They say our language is lost. It is lost means it’s still somewhere, but we just, we need to find it again, right? And, and that I found very striking because in, in linguistics, we always talk about, Oh, these are moribund languages. There are just a few speakers left.

When those speakers are gone, this language will become extinct. It will die out. I think for, for, for the Kusunda at least, this was never really like, it’s extinct. It’s just lost. It’s still there somewhere. And we still have the opportunity to retrieve it. And in that way, it’s far less final, far less irrevocable in the sense.

And I think that is also what encouraged. A lot of the Kusunda people and the requests that they made, please, can we, can we revitalize our language again, because some description is there, some recordings are there. So in one way or the other, we’ll be able to to again have a normal speech community.

So yeah. Let’s see how the future holds for them, whether they’ll be able to actually make that speech community. And, and they’re saying like, we should actually all move together, all Kusunda people, 161 Kusunda people, we should just stay in one settlement, integrated settlement, where we can where we can have our schools in which we can teach our language and in which we can show tourists or scientists, academics or whoever is interested, like how we used to make those lean to huts in the forest and teach them about our language, etc.

So they have this, this idea of a kind of a reservation or a kind of a homeland or an integrated settlement. I think in, in, in the Western sense, you, it, it sounds a bit It sounds a bit negative, like you get connotations of forced relocation of people into reserves but for them this is like, okay, this is how we could probably try to, again, revitalize our language and our culture by, by living together instead of in all these scattered, scattered settlements where they also live on, on very Insecure land tenures, for example, where they don’t actually have full ownership of the land, and they can be, they can be basically be sent off the land at any moment.

So for them, this is, this is like, okay, if we have this kind of an integrated settlement, it will, it will mean a lot to us. So let’s see how the future holds for them, whether it’s possible to achieve that.

Olivia Clementine: Where is your path heading right now in terms of your linguistic work?

What are you interested in supporting?

Tim Bodt: Ultimately, of course, the, the, the wish to preserve the language should come from the speech community itself.

So as an outsider, we are not in any position to say, Oh, you should. You should preserve your, well, of course you can say that because there are, there are other motives behind it than just the, the, the community mode, right? Or you can also say like, oh, go from an academic perspective or the value that this language has for the whole of humanity should also be taken into account in, in, in trying to promote the language.

But ultimately the ones who have to retain, maintain their language is the speech community itself. So they should find the value. When I was working on Duhumbi, for example, people were saying like, okay, but our children still learn the language. So there’s no danger there. We don’t, we are not worried about our language becoming less and less spoken over the coming years and finally ending up with no one speaking it anymore.

But. Experience has shown that this can go very fast and that people don’t really realize that it’s actually happening. And, and one, one big advantage of doing linguistic fieldwork and writing a descriptive grammar based on a corpus of texts, recordings, making things like a dictionary, a storybook, at least you keep the options open for future generations to to revitalize.

Or if it’s, if it’s no longer spoken, even to awake their language again, and you can see that, for example, communities in, in, in North America indigenous communities in North America, or in Australia, that that have no speakers left, but there have been some records, written records, sometimes from a very long time ago where these On which they can use as a basis for actually teaching the language again.

So even if the community is still there, but the language has gone, if there is some kind of a record of it, then it can be used to used to introduce the language again. So I think that’s, that’s, that’s very well, I would like to continue with at least giving people the future opportunities, speech communities, the future opportunity to, to, to, to work with their language by keeping a record by language documentation, description and also already prepare materials that, that will more directly benefit the speech community itself because a linguistic grammar, an academic work is not easily readable by someone who doesn’t even know English, right?

So. I, I’ve made a dictionary of the Duhumbi, for example, a storybook, just to give something back, there are pictures in it, it’s written in, in their own language, in, in the Roman script, it has a translation in English, translation in Hindi, so they can learn about the, the stories that were being told before in that way, and I would like to, yeah, I think it would be, there are so many languages still yeah.

left that have not been described at all in the whole world, but also especially in the Himalayan region, even in that module region in Bhutan, in Arunachal, there are so many languages that have no description at all, or a very short description, maybe sometimes just a word list. And the communities themselves are interested to to, to have descriptions of their language, but they just don’t have the capacity because they’re busy with daily lives, with survival.

They don’t have people educated enough yet to work on this. So, yeah, I think if, if I could make a contribution there, then I think. That would be very satisfying in many ways. So more descriptive work, more comparative work, maybe try to find out where people came from. Because also from a scientific perspective, of course, this whole migration history of such a an interesting region, like the whole Himalayan region, that’s also something that I’m interested in doing.

Olivia Clementine: Sounds very exciting. You have many trips ahead of you.

Tim Bodt: Hopefully. Yes. Yeah. No more pandemics for me. Thank you.

Olivia Clementine: Yeah. Yeah. I think for everybody. Let’s hope. Yeah. Is there anything else you want to share? Anything else that’s fresh in the mind.

Tim Bodt: I would really Encourage you to travel in Arunachal Pradesh and see there if you have the opportunity and yeah, if you, if you want to learn a language, you should never be afraid of making mistakes.

I think many people. Especially maybe because also because we have been taught languages through the formal system, like with textbooks and with, in those days, cassettes. I’m sure now it’s all on the laptop. But yeah, in a very formal way, learning the grammar, learning the vocabulary, maybe not that much speaking practice.

So I think that, that Learning a language is very much about just talking and not being afraid to make mistakes. I’m, I’m a native speaker of Dutch. I, I, I kind of have the impression that my English is pretty okay. But even in Dutch and even in English, I still make mistakes. Plenty of mistakes, I’m sure.

And it’s the same with Nepali, with my Tibetan I make mistakes. But in the end, it’s about the message, getting a message across. Right. And as long as people understand each other, making mistakes is not a problem. And I’ve always people have never, not talk to me because I would not speak their language properly.

So that’s, that’s, I think that’s very important to realize. Don’t be, the very fact that you’re trying to speak someone else’s language is already so much appreciated that they don’t really bother about whether you speak grammatically correct. Like you make small mistakes, you may even make big mistakes.

As long as people still understand what you’re saying. If I say, Oh, he was hungry right now. Me can eat things, anything, then you would still know that guy’s hungry, right? Let’s give him something to eat. So in the same way, like. Making mistakes is not a problem. Get the message across. That’s the important thing and, and let, let not being able to properly speak a language not, it should not prevent you from actually trying.

And for, especially in the Himalayan region, people are always very very appreciative of people who make an effort. An effort and we try to learn their language and to try to speak their language.