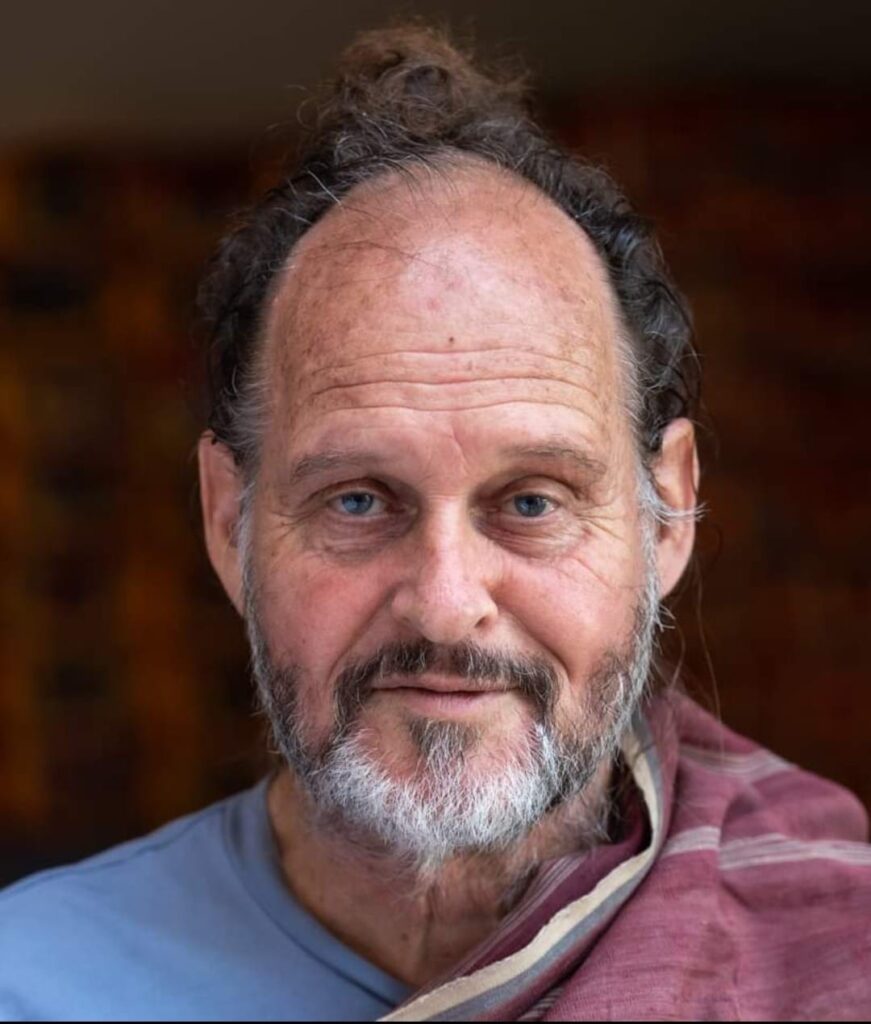

Erik Pema Kunsang is a dharma teacher, practitioner, and a reknown and prolific translator of Buddhist texts and teachings.

Some of what Eriks shares:

00:01:00 On serving and translating for Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, clairvoyance and what is needed for liberation.

00:04:00 Dzogchen person versus a dzogchen teaching from Trulshik Rinpoche

00:08:00 Styles of teachers and busy not doing anything.

00:11:00 Misunderstanding the nature of superficial reality and dharma bums

00:14:00 Bodhi Training

00:16:00 Describing reality

00:17:00 Using the mind as the tool. Moving towards certainty and out of vagueness. The benefits buddhist meditation rather than science.

00:19:00 About fruitful intimate relationships as part of the path of being a decent human being, not breaking trust and learning to live together.

00:23:00 The yanas including Manushayana and Devayana.

00:28:00 Split between real world and spiritual world

00:29:00 Using our meditation and spiritual practice time well. Changing karmic patterns

00:32:00 What it really means to be civilized

00:34:00 Essentials for translating genuinely

00:35:00 Leaving nature to itself and no-dig gardening.

00:37:00 Closing statements on landing timeless value systems of the Buddhas

Erik Pema Kunsang has studied and practiced the Buddha dharma and especially the teachings of Padmasambhava. He has been trained by many masters. including the Dzogchen master, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, as well as his son, Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche. Erik helped bring about Rangjung Yeshe Institute and publications for both study and translation of Dharma. He has translated and published over 60 volumes, including his freely available Tibetan English dictionary. Erik is also the founder of Bodhi Training and is currently the resident teacher at Rangjung Yeshe Gomde Retreat Center.

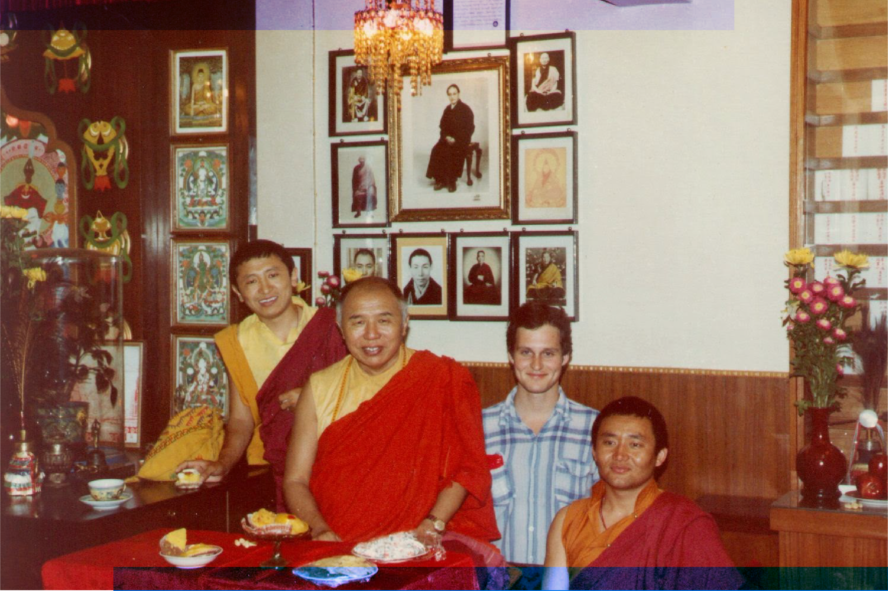

First image was from Khyentse Vision Project.

Links:

Bodhi Training

Gomde Denmark

Support

Enjoy these episodes? Please leave a review here. Scroll down to Review & Ratings. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/love-liberation/id1393858607

Transcript: (please excuse all errors)

I’m Olivia Clementine and this is Love and Liberation. Today our guest is Erik Pema Kunsang. Since 1972 Erik has studied and practiced the Buddha Dharma and especially the teachings of Padmasambhava. He has been trained by many masters. including the Dzogchen master, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, as well as his son, Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche. Erik helped bring about Rangjung Yeshe Institute and publications for both study and translation of Dharma. He has translated and published over 60 volumes, including his freely available Tibetan English dictionary. Erik is also the founder of Bodhi Training and is currently the resident teacher at Rangjung Yeshe Gomde Retreat Center in his native country of Denmark. This conversation was in person in Denmark, following a retreat that Pakchok Rinpoche and Erik Pema Kunsang co taught. The sound quality in the beginning is not so great, but keep listening. It improves very quickly. Olivia Clementine: So perhaps we could go back to the beginning of your Dharma path or official Dharma path. A huge part of your life has been your connection with your root teacher, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, as well as Chokyi Nima Erik Pema Kunsang: I’m connected with many other teachers, also but I spent most time with Chökyi Nyima Rinpoche and… His father Tulku Urgyen. Tulku Urgyen presented what he knew, he almost never used a text. And when he was pressed to teach in a text, he would just read it loud and say, impossible to say anything better than this. And then put it like this, and then we finished reading it loud, and he just gave it back, and that’s it. I don’t have anything to add. So, quickly we found out that it was much better to ask one question, and then he could speak for one hour. Laying out the complete vista, the landscape, based on that one question. Later it turned out that often he had answered everybody’s questions. questions just by doing that. So he was remarkably clairvoyant without ever claiming that. But people who were close to him, they had no doubt about it. But if you didn’t ask a question, he just said he was content just being present. If you engage in conversation, it’s just, have you had anything to eat? How long time since you came to Nepal? But not asking what they want in life or anything like that. Just sit there and after a while it will be quiet. And people who didn’t know better. You will get uncomfortable. Stand up and walk out. But if you ask them a really subtle question, then he will be very happy. The more subtle and difficult, but the better. But based on the experience. Not theoretical things. One time a young not Kenpo yet, but hatching to be a Kenpo, he asked do you have a question? Yes. – said, is the Buddha’s perception direct or through inference? And then he got a half an hour scolding, of wasting the time, his own time, and teacher’s time, with speculations never came back. we don’t get liberated through speculations, but through, certainty in your immediate experience. That was what matters. That was his task, his pledge in life is to deal with people’s state of mind and then clarifying that in a way so that they could continue using that for, for the Meditation practice. Olivia Clementine: And you spoke the other day about when Rinpoche passed and you were processing his passing and it was a really difficult time for you. And you met with Trulshik Rinpoche. And he spoke to you about Dzogchen person versus a Dzogchen teaching. Erik Pema Kunsang: You can hear it from when people talk about Dzogchen, they speak about it as if it’s something else, something looked at from a distance in Dzogchen, they always point over there. In Dzogchen there is no cause and effect, stuff like that. But it is to go about it in a completely wrong way, because dzogchen is not supposed to be that. It’s supposed to be this. And that’s how it’s being put to, to use. It’s in the mind or in the heart of the individual person. They want to write dzogchen as a landscape that is restricted to great masters like incarnations of Vimalamitra and Padmasambhava. Nobody else. It’s not their business. They cannot speak from above. They can only look like from where they are and then it’s always very limited. So to make oneself the spokesperson of dzogchen. Dzogchen is like this and this. It means you have visited that country. Which is called Dzogchen. So you know what you’re talking about. But the fewest people are like that. So it becomes a lie. Like talking about a place one hasn’t been. And it’s fooling oneself and it’s fooling others who then come to listen. You want to hear about dzogchen from somebody who doesn’t know. that’s, that’s wasting teacher’s time is wasting people’s time. Even though, Trulshik Rinpoche just said a few words, it has stayed with me all these years as a kind of a, a certain kind of stone you use to sharpen a knife. It’s good to have that, so that you can grind, even though it is painful and scratchy and makes an awful noise. But unless you have that, the knife doesn’t get sharpened. Sometimes teachers have to be seemingly unkind in order to get through. Thick skulls of westerners. Seemingly unkind. It’s actually very, very kind. Tulku Urgyen would never say anything like that. So one could be a delusional, dzogchen, quote unquote, person, and, for years, and not notice it. He was like that. If you want to be deluded, then you’re welcome. If you want to be more earnest, you’re also welcome. All teachers are different. It’s a combination of their past decisions, wishes, and their upbringing, and their lessons. You can see they’re built, and what they’ve gone through in their own practice. And whether they’ve studied a lot or studied a little. And they’re just a general character. Whether they’re bold or timid. All are different. It’s not that the Masters go to a dzogchen school, and they come out as a clone of that. system. It doesn’t exist like that. And that’s wonderful, in a way. Olivia Clementine: Yeah, I guess I wonder, too, for you, like, if you were drawn to certain styles of teachers at different moments in your life, because you’ve studied with so many different teachers, like, you needed maybe more seemingly unkind teachers at certain moments. Erik Pema Kunsang: Maybe I have written on my forehead, handle like egg. So they be very, very sweet. I think I needed that in order to feel safe. But that’s just me. Some people, they actually appreciate a little kick in the butt. I don’t appreciate that. But Chökyi Nyingma Rinpoche, he can be sturn by just a look, a glance, where you say something, and he just has to look at you like that, and you know it was really stupid. So you’ll never say it again, like that. But he doesn’t have to reprimand you. Some people he will reprimand, but rarely. Rarely. Whereas his brother ? Chokling, all different ways, sometimes really crude, sometimes he would just send a, a monk out and say, Rinpoche is busy. Then I would walk in because I felt entitled. I lived next door. And you see he’s not doing anything. But he’s very busy not doing anything. Like ministers or people from royal family in different countries. He was often too busy to meet. Whereas a beggar or… Sometimes Sadhu Baba, he would spend hours with, talking nonsense. And as a demonstration of everything being illusory, I saw him once talk with another yogi about the shape of a cup for half an hour. And it was completely… Enthralling. They, they really went to it like, how special that cup is and the shape and the… And then you just laugh at the end. And forget all about it. It was like an exercise in superficiality. But at the same time getting into it with heart and soul. And I think that’s a wonderful demonstration of how seeming reality is unimportant. And but at the same time giving it full attention. And, and at the end just laughing their heads off. Because they’ve been able to keep their keep their cool for so long. Taking it seriously when it’s completely pointless. How to take the pointless with a certain seriousness is not easy. When you see it like that, people usually, they, they stay away from and they begin to hate the world, the world, so to speak. Hate things, hate fame, hate money, hate enjoyments. Well, that’s demonstrating that one hasn’t understood the nature of superficial reality. If you put so much seriousness into it, and you hide away, and you don’t talk to anybody. A lot of westerners I’ve met, they fall into that trap for a while. And then when they get out of it, they get totally sucked in to the other extreme. And Chökyi Nyingma Rinpoche, he he sees all that. So at some point, he, he, he said, we need to do something for the Dharma bums. They come to the East, they spend years and years, getting into their own understanding of the Dharma, and cultivating that as you would cultivate a garden, but they cultivate the thorny bushes as if they are special flowers. They cultivate smelly flowers as if they are the most fragrant. Why? Because they haven’t learned from a real teacher. They just travel around and try to follow what they picked up in the in poetry books and biographies. rAther than learn the Dharma, they They prefer their own version of of what the Buddha’s teachings are. So he said, we have to do something about that. I’ll start a school. So then he started Rangjung Yeshe Institute. It took some years getting off the ground. But it got established in the 80s, early 90s. And he was very happy that people would come to the east, and then spent out of three months in Nepal, they spent two months studying something, discussing it, and at least when they return, they will have something under their chest. So, and that has developed now. Now he’s branching out and making a second institute in Austria, in England, also when that gets possible. Not here. Not here. Olivia Clementine: Well, you have Bodhi training. Erik Pema Kunsang: It’s too small. It’s too small. Yeah. Yeah. We don’t have facilities like that. Yeah. Bodhi training is something It’s a mixture that I haven’t seen anywhere. It’s a mixture of the simple meditator together with a little bit Pandita style, but fused together. So rather than going through books, As an academic study, you study your state of mind with analytical meditation, but during the meditation state. So it’s kind of a fusion, and it’s adapted to people who have jobs and family. So, try to make the best out of the short time a normal person has. Still gaining some insights that are totally traditional. Like I mentioned the other day, the Four Seals of the Dharma. Topics like that we’ll cover. Which are very traditional. But still examining it in your own life situations. Rather than saying you study a text. Then you study your life and your mind. And I found that to be very fruitful for some people. Some are really saying, but we don’t get anything of real substance. But what substance is there to get? There’s your life. And find out what it is. Luckily it’s not so long, so they can just go on to more. Detailed studies, if that’s what they want. But often people don’t know what they want. Olivia Clementine: The other day you were speaking about inner and outer, and you were saying that they’re not accurate words, but we have to use them. Would you elaborate on that, because we use these terms outer and inner all day long, especially in this realm of conversation. And I’m wondering if there’s any trouble with that language, and also any other words you would recommend using instead. Erik Pema Kunsang: It’s perfectly alright to use inadequate words, because all words are inadequate, when it comes to describing reality, which is basically beyond words. There’s nothing to do about that. So, since we have the tool of language as human beings, we try to make the best of it. Outer and Inner is used in many cultures, to refer to how things look like when many people describe something in common. That’s called Outer. We’ve seen it from the outside. And also yourself is seen from the outside by other people. That’s called the outer level. The inner one is seen from the inside. When the mind looks… The problem is just that people in the West are not aware of their own minds. They think mind has to refer to something that happens in the brain. Immediately making it into an external thing. It’s a mess, it’s a mess of vagueness, and that has to be cleared up, and be led towards certainty rather than vagueness. Often if you ask people a direct question about what are you then they don’t know what to say. It’s a blank, it’s, it’s vague. So, Buddhist meditation instructions can help clear up that vagueness, and make the person know what they are talking about when they have simple conversation. When I say, how are you, then they can actually say, How they are, rather than going around in circles and then finally coming with some scientific description about how they are, which is not their reality, somebody else’s description. But somehow that is taken as more valid than their own immediate experience. This is a modern life. Like the blind leading the blind. And that is… is an area where Buddhist teaching can be come to good use in, in the West, because science hasn’t picked up yet, that yet. They still think we have to look through tools to see reality, microscope, telescope whatever, rather than using the mind as the tool. There’s a lot of… room for improvement. Olivia Clementine: You’re in what I would term an inspiring relationship with with your wife. I wanted to see if you’d be willing to share the significance of intimate relationship for the path of liberation and just for the betterment of society as a whole and anything you’ve been learning along the way. Erik Pema Kunsang: The first level of two human beings staying together is to use teachings I call the human dharma, dharma for humans. ANd the main points I’d like Phakchok Rinpoche mentioned the other day, the basic human values, being considerate and tolerant, broad minded, Trustworthy. Those kind of qualities we have a really good chance of developing with another person. Why? Because we are confronted all the time with our shortcomings and we have to have a willingness to overcome them. Then a relationship is very fruitful because we remind each other on how to be a decent human being. Kind hearted, decent human being is worth a lot. Not only dealing with situations, but dealing with ourself, dealing with another human being. There has to be some kind of respect and openness towards that. Not only through self help books, but making an effort. on a daily basis and that effort is based on your decision, your will. You have to want to be a decent person. So you make that and not a sullen vow and not like that. But that is your aim. You cannot stay with someone unless you have that kind of decision. I, I use the word Mönlam in in English as decision, wish, fused together. Because it’s both a wish, like, wishful thinking, but it’s also a decision. So, those two together guide our behavior speech patterns, and attitudes into the right direction, so the other person can stand being together with you. And that is in rare supply in the world. Most couples, they split up because they don’t have that willpower to be a decent person together with another who has feelings and gets hurt and like that. For example, there’s no, often no decision which to be sweet when it hurts. You get some abuse, you immediately answer back with another abuse. That is called breaking the trust. And then it’s difficult to be together when there’s no trust. So the very first abusive word, abusive behavior, and of course it springs from abusive attitude. That is how relationships get destroyed. And avoiding that is a very important part of being able to live together. So I would love if people learn that. Before mathematics in school, before, because it’s more important, how to live together with another human being. And it starts in the classroom. And often bullying is considered alright, as long as there is no physical beating. And it’s not alright. Olivia Clementine: Have you noticed studying reality through Dharma practice, or that path of reality, has it changed your way of doing relationship over the years? Erik Pema Kunsang: My wife is my teacher of that -. Chökyi Nyingma Rinpoche is teaching that. Dalai Lama is the main teacher of that in this world. In the He just called it that. It’s a word I have from – Rinpoche. The two vehicles before Hinayana. Manushayana and Devayana. For human beings and for divine beings. And here divine beings are not some other beings in the God realms. It’s you. But you begin to notice the endlessness, the infinity, the divine quality in the present moment when you rest in yourself and let it expand and open up. Then the instructions for devas become really useful. How to be in the moment, in the present, in the real sense. Not just as a nice idea. I live in the moment, but actually you’re just as bad as anybody else. But you spend time in meditation and then you let the present moment expand and so there is room for the boundless qualities of love and kindness. Like that. It becomes part of yourself. It has to be part of your daily experience before entering Hinayana. Otherwise, Hinayana gets weird. Hinayana is a teaching that is sublime in this world. But it’s not for people who haven’t become decent human beings, who are willing to steer clear of troubles. And it’s not for anyone who has not… some contact with the divine qualities of, like the four, the boundless. Not as an idea, but as yourself. Then you can begin the Hinayana discovering the absence of personal identity, which is nowhere to be found no matter how much you look. That, without that discovery, of the egolessness, mahayana is impossible. It becomes fiction. Just words. Empty words. Forget about Shunyata. Unless you are a decent person with personal experience of boundless kindness and compassion and without the experience of the unfindable quality of me and I, myself. Then there is no Mahayana, it’s a fiction. And without Mahayana, there’s absolutely no Vajrayana. So, any good teacher would always lead the students through that. Some are already quite far advanced, even though they’ve just come in through the door. Nobody, nobody can judge that, except a good teacher. But it has to be covered. Otherwise you have, What is called vajrayana assholes running around un bridled egoism and calling it vajra rituals, vajra pride,, and all that kind stuff becomes a way to undermine the work of great teachers. Does it sound like scolding? Olivia Clementine: No. It sounds very compassionate and direct. Erik Pema Kunsang: So that’s what I’m trying to incorporate into Bodhi Training. We start with Dharma for humans, and then slowly Dharma for Devas, or Gods. God then means the divine dimension that everyone has access to, which we don’t learn in school. More than the good heart, it’s deeper than that. It’s a good heart as a dimension that we can uncover in ourself, and it’s worth a lot. It’s the domain of past saints, no matter what religion they belong to. They all agree on those. And Huxley’s perennial philosophy, he discovered that as his life work. And many, many other great Teachers and through the ages they have taught that. And human beings are inspired by that because hearing it from so many angles, it rings a clear bell into what people feel from time to time in their life. Then you can get into Hinayana. And Hinayana is not a lower vehicle as it’s looked down upon from Mahayana. It’s a Buddhist teaching to some people. And some people at a certain level of development, then they expand that and then all of a sudden they’re mahayana people, but it’s the same person. It’s not that hinayana some countries or it’s them people. It’s the individual mind that’s being talked about. Vajrayana is the individual mind. It’s not somebody else. Olivia Clementine: It seems like in the modern day, more people are able to do all the mental things, like to, to do science, to talk about being Vajrayana people, but what is it about our obstacle of, of dropping into practice and actually doing practice? And I think it seems like in a way, less attainable, even like less attainable to be ourselves than to go do the modern day kind of getting of intellectual things, getting persona. Erik Pema Kunsang: I think one of the main obstacles is the split between life, the real world, and then the spiritual world. There’s no two worlds. It’s exactly the same you in both situations. And that split between the… Being a Dharma person and then just being a person. It’s a fictional split. It’s not a real division. Like the way you treat a dog and the way you behave on the meditation cushion. It’s not two different things. You should actually treat your mind as a dog. Because it’s just as naughty. Misbehaving or well behaved, it is something to do with sweetness and tolerance and giving room. And those kind of qualities we should begin to see as genuine Dharma practice. To allow sweetness, giving room, and being more tolerant. That is often a real Dharma practice. Rather than how many minutes you sit. The closed eyes, like that, may not change you that much. It changes one thing, you have 30 minutes less of your life afterwards. That’s a change. Olivia Clementine: If somebody wanted to use their meditation practice and spiritual reflection time well, like not waste all that time, because I think many of us do, just sit and just, Oh, I did the 30 minutes, I did the hour, I did the hours. What would you suggest in terms of a reflection, or a way to use that time to keep the fire of reality there? Erik Pema Kunsang: First to start with good wishes, and then turning that into decision wishes. Where it’s not just hopeful hopefulness wishful thinking. But it turns into a decision. And that decision, your will, is your most… accessible tool to change your life. This is how we change our karmic pattern. The first, most obvious of the four veils, the karmic veil, is change through your willpower. You can say, oh, it’s bad to take lives, but that doesn’t mean that you stop. It has to be your decision wish, as much as possible. Even the smallest life, I will try not to squash. That will change your karmic pattern. So there has to be willpower and decision wish. It’s very important. That’s starting from the, you see, if something has many layers of shell, that’s with the outer level. And making decision wishing is about the opposite. Whenever I get the chance to save just one life, then I will not shy away, I’ll save that one life. Like fishing up an insect from the swimming pool and putting it up on dry land. Some people think that’s useless, especially if one is in the habit of exterminating lives. Just like the word was used in… Extermination camps. People think often that extermination is good. But everyone wants to live. If there are some really giants coming, and they think we are the ones that need to be squashed, and to clean up, then we wouldn’t like it. So, start from where it’s possible. And then, at the same time, savor the goodness that becomes, You can taste it when you save a life or when you just stop not squashing some innocent on the road or where you, people like to do jogging, but that means you don’t see who you’re stepping on. I’m sorry about So maybe other kinds of exercise is better than just running around blindly and stepping on you can walk, but walk gently. Open doors gently. Close them gently. Speak gently to each other. In other words, become a gentleman. Or a gentle lady. That’s really important. That belongs under human Dharma. It’s really important to have a society of gentle, really civilized people. Not just being able to read or write. That’s not called civilized. Civilized means to be civil. Not civil as opposed to in uniform. But civil and polite, considerate, and taking care of each other. That is how human beings are supposed to be. Humane. Yeah. Taking care. That, I think, is really, really important to teach young people and teach each other. And especially, as you mentioned, to be in a relationship, you have to be civil. It’s really important. Otherwise, you get kids, and then you find out you can’t control yourself. And then then you get divorced. Because you can’t stand yourself in the company of another. Blame the other person for that. Olivia Clementine: So, in regards to translation, what would you suggest, any advice to translate genuinely and not miss the point? Erik Pema Kunsang: Point number one, be kind rather than a stickler. That’s the most important. Kind meaning you care about the other people understanding, rather than just being right. And what is right is based on what you know, which is kind of limited. We know really a small fraction of the Buddha’s teachings. And there is a cause of human nature is to blow that up. Studying the university, one tiny little text, and you maybe did an B. A. or M. A. on that, and then, wow, the whole world has to be fitted within that little topic. That’s not kind. We actually wasted years on that. Much better to study something that is of real value. Real value. How the human mind behaves, and how to steer that in the direction where it’s the most beneficial. That should be the main topic, because that is Dharma. That’s the point of Dharma. And if you think about it, it’s obvious. Then, later, we feel we have not wasted our time. The same with the science, doing research on the green frog. And how it jumps, stuff like that is completely useless. You could spend time finding out how to improve the quality of life for everyone. Something universal, rather than something limited and specific. Nyoshul Khen Rinpoche, he once imitated the woodpecker. Tick, tick, tick. And check, check, check, and the box come out. And then the scientist sitting and taking pictures of that and writing down how many times it does it. And he said, totally useless, totally useless. But it’s so interesting. No, it isn’t. You get your grant, you get your scholarship, and then you spend time. Erik Pema Kunsang: And you get a degree so that you have a name to make yourself feel that you didn’t waste your time. But it’s totally wasted. And that’s called science. Many cases. Olivia Clementine: Do you feel like if person was supporting saving the ecosystem of that area, that would be a use of time? Erik Pema Kunsang: Of course. But the ecosystem, It gets ruined by you coming in and studying it, often. Things left to themselves, often the best way. Are Olivia Clementine: you still doing no till farming? Erik Pema Kunsang: Yes. Well, it’s not easy to, people, it’s hard to get everyone to agree. I did, we did no dig our garden on Fyn, yeah, and it amazing how much thing, vegetables grow compared to the flowerbed right next, where we didn’t do it, so it’s, when children are allowed to discover this, then they, they don’t need convincing, it’s becomes self evident. Those, those things, use the extra, the surplus, as fertilizer, rather than carrying it away. Like it’s usually done in gardens. You mow the lawn, then you have something that picks it all up, and then you throw it out and pay to have it carted away. Olivia Clementine: Is there anything else you want to share? Or any other aspirations or misunderstandings that should be clarified before we close? Erik Pema Kunsang: Yes. Something I mentioned one of the other days. Which was, to any of you who are concerned with landing the timeless value system of the Buddhas, more than one Buddha, the Buddha Shakyamuni, past and future Buddhas, then be concerned with first of all understanding basic human values. That’s the first thing the Buddha taught. And, which is for everyone, not only for Buddhists. Something we can all agree on. The, the humane common denominators. That’s the point number one. And then expanding that to those who are interested in going deeper in the Buddhist teaching, making room for that. You don’t have to call it only Buddhists because it’s… Just going deeper into the study of reality with the help of the Buddhist teachings. That I would like to be grounded or landed or established in our world. But please be kind and not a stickless. Be kind in the sense that don’t use difficult words that you have to go to university in order to understand. It’s unnecessary for the human mind to understand something. It doesn’t have to be said in Greek or Latin or Sanskrit or Tibetan. It can be said in straightforward language. So please be kind. Olivia Clementine: Thank you so much, Erik. Erik Pema Kunsang: That was not kind. Olivia Clementine: No, it was really, seemingly unkind. Yeah. But kind.