~

Some of what Carroll shares today includes:

00:00:00 From New Jersey to Nepal, a nunnery, her future husband, and the 1985 Kalachakra gathering.

00:08:00 Stories of meeting her teachers, great meditation masters, including Dilgo Khyentse, Bakha Tulku, Trulshik Rinpoche, and Lama Wangdu.

00:17:00 Advice from His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

00:19:33 Taksang (Tiger’s Nest), the Nechung Oracle & receiving Dilgo Khyentse full terma.

00:23:00 Innovation, monasteries, and keeping the dharma meaningful and safe.

00:25:00 Stories and memories of Trulshik Rinpoche

00:30:00 Learning Himalayan languages

00:33:00 Humla and how it is unique

00:35:00 Dragon Brides; on polyandry, women with many husbands

00:40:00 On her meeting and marriage with her husband Thomas Kelly

00:43:00 Fostering children and non-dual gifts of Nepal.

00:49:00 The market economy’s impact on relationships, Earth, and family structure.

00:56:00 Notions of modernity disguised as freedom.

00:57:00 Raising children in a seasonal manner, rituals, healing, and rites of passage

01:09:00 Best place to give birth and to die.

01:10:00 Relationships, healing, mistakes and safety in anthropological work

01:20:00 Nepal’s ethnic diversity and environmental challenges

01:27:00 Longevity, biomimicry, meditation and aging

01:30:00 The origins and journey of clothing.

01:38:00 Innovations of waste and creative change agents in the textile industry

01:45:00 Risk, collaboration, and the unexpected amazing.

~

Images are thanks to photographer Thomas L. Kelly who is also Carroll’s husband:

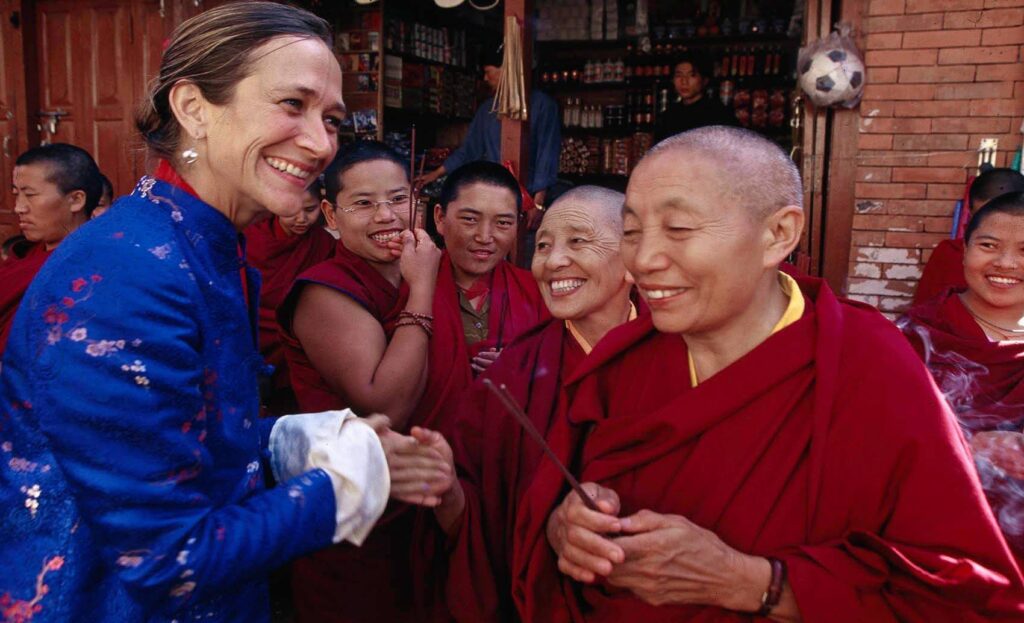

Trulkshik Rinpoche & Carroll

Chopon for Machig Rinpoche, fire puja offerings to the Nagas (Lu) Goa, India

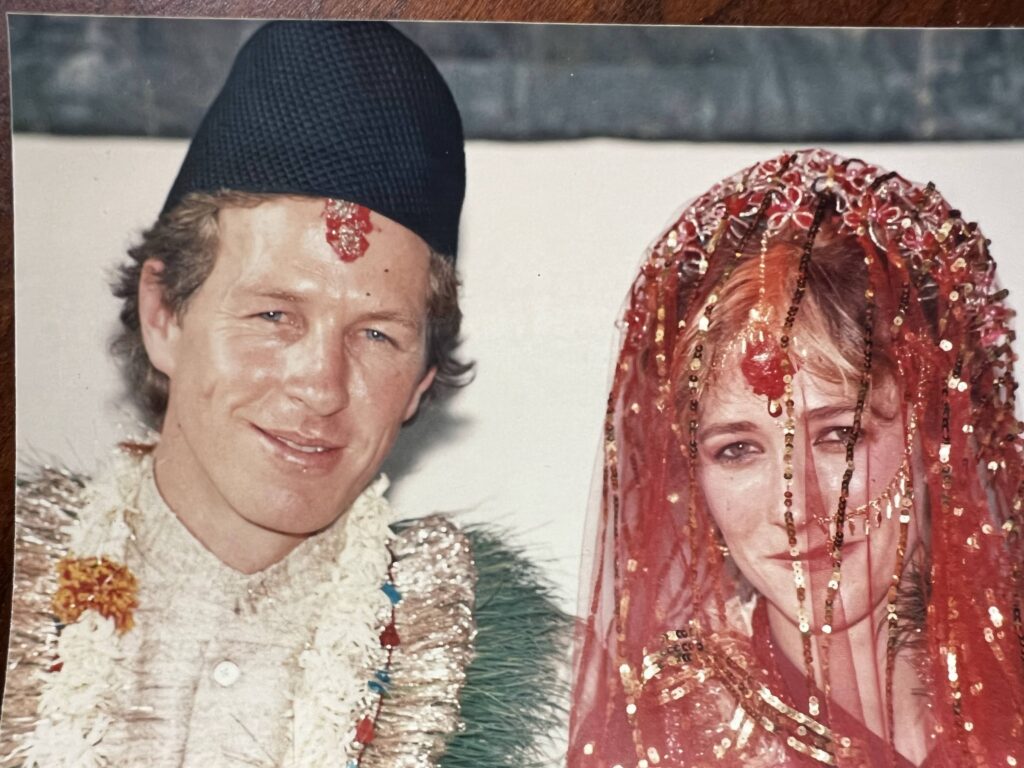

Thomas and Carroll as bride and groom

Tsang with Carroll & son Liam, Dakpa, Nagarkot

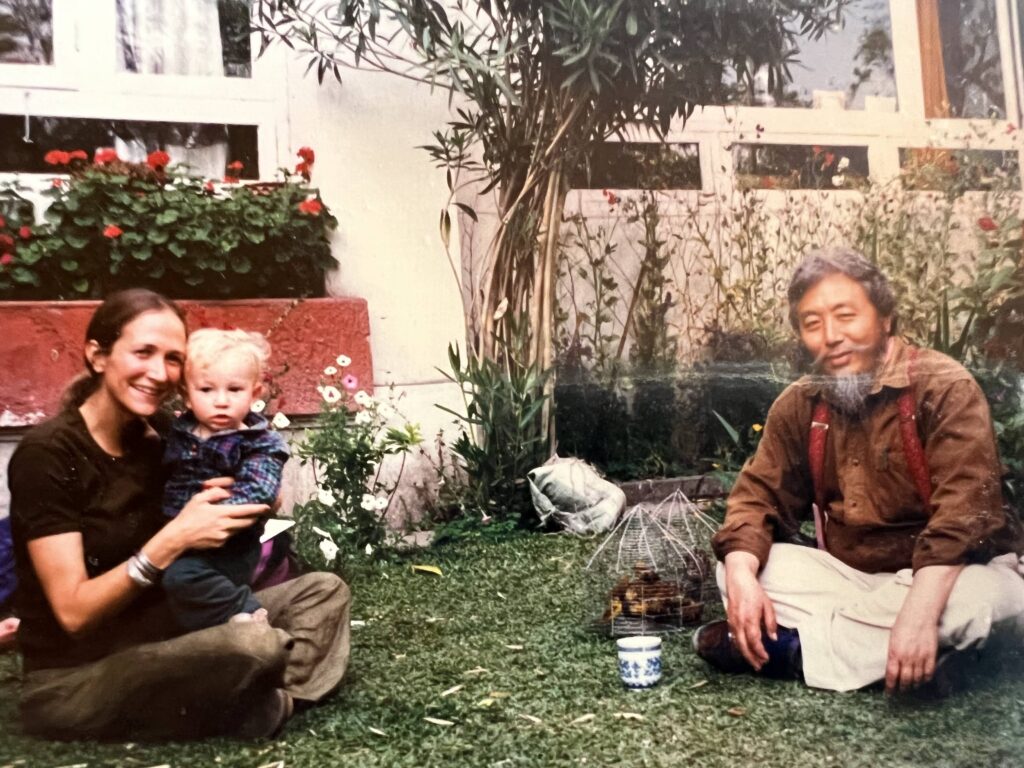

Carroll, Liam, Bhakka Tulku bird release Dilli Bazaar, Kathmandu 1991

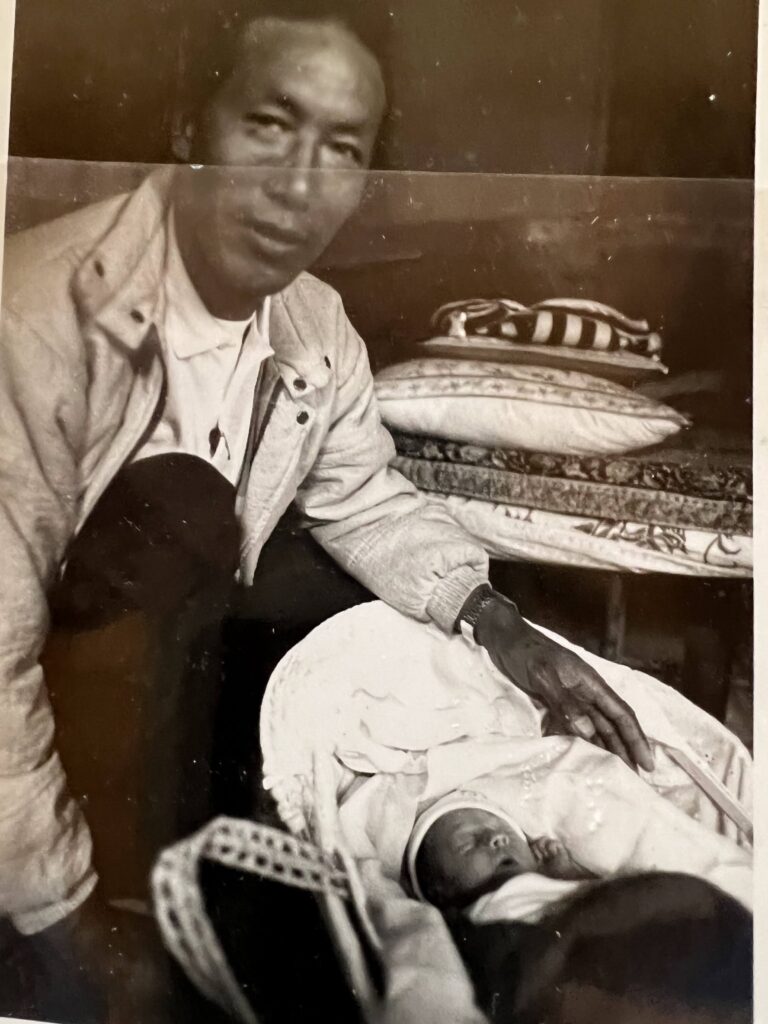

Baby Name Ceremony with Amchi Tsampa

Blessing stove in their gher, with children Galena and Liam, and Gerlee, Toro’s Mom, Step Dad, Toro who built their gher

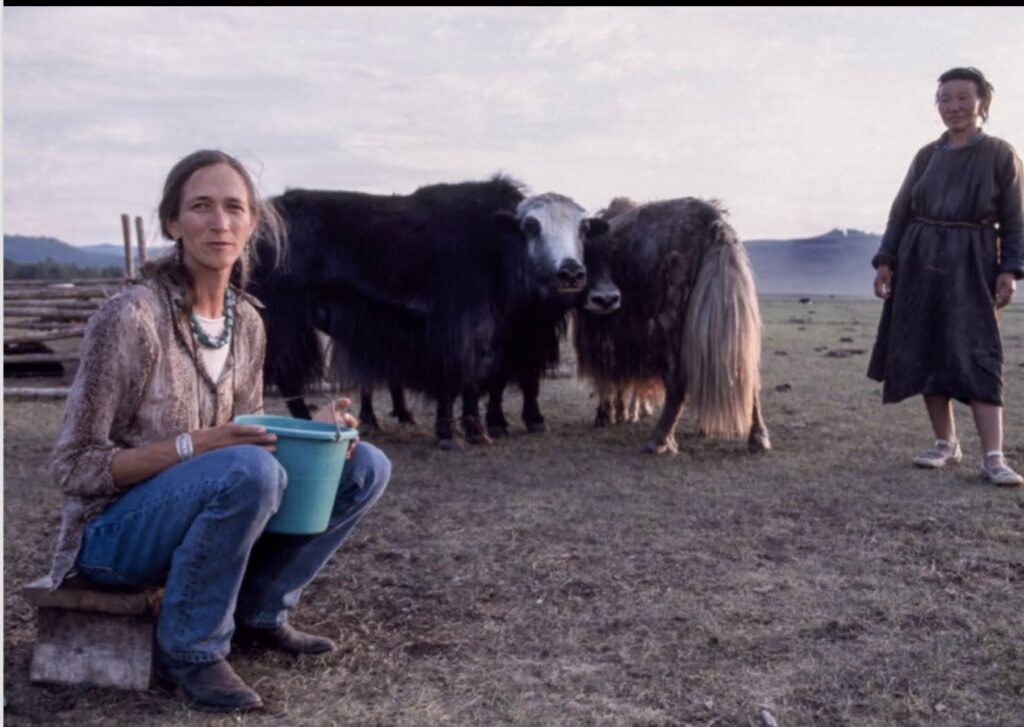

Pagma teaches Carroll how to milk yaks

Conclusion of Riwo Tsang Cho Puja, Yoga Retreat

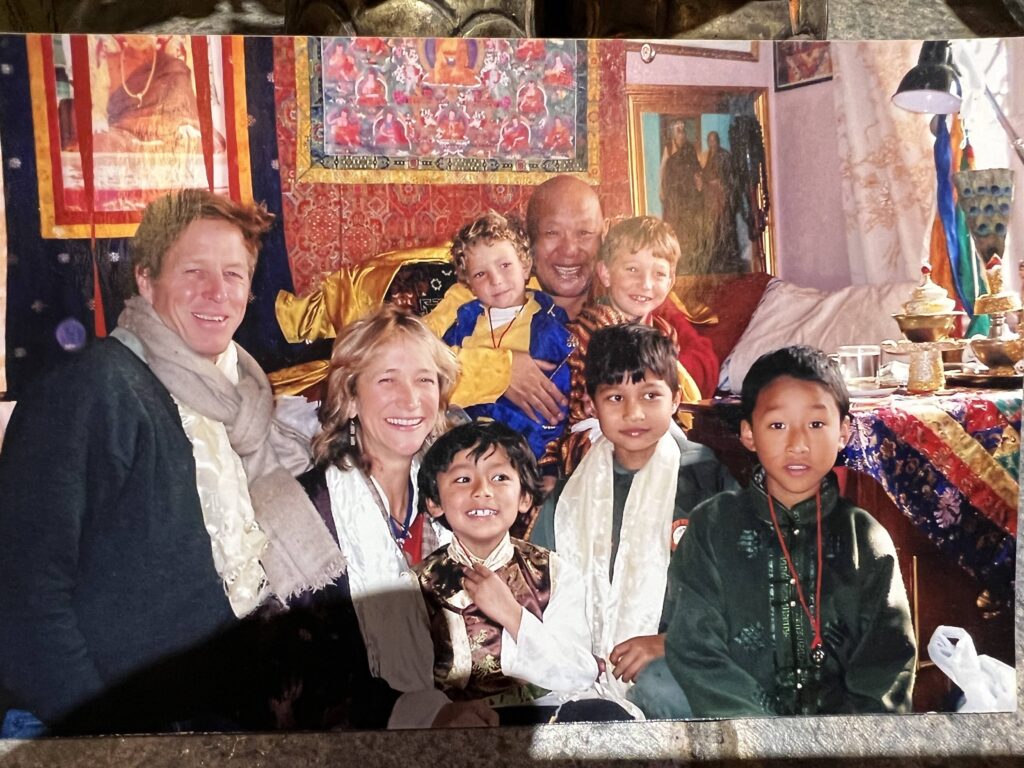

Family & Lama Tsering Wangdu

Dartagnon & son Liam, Orkhon Valley bareback

Liam and Galen, Shivagiri, Gahana Pokheri, Bai Tikka, Nepal

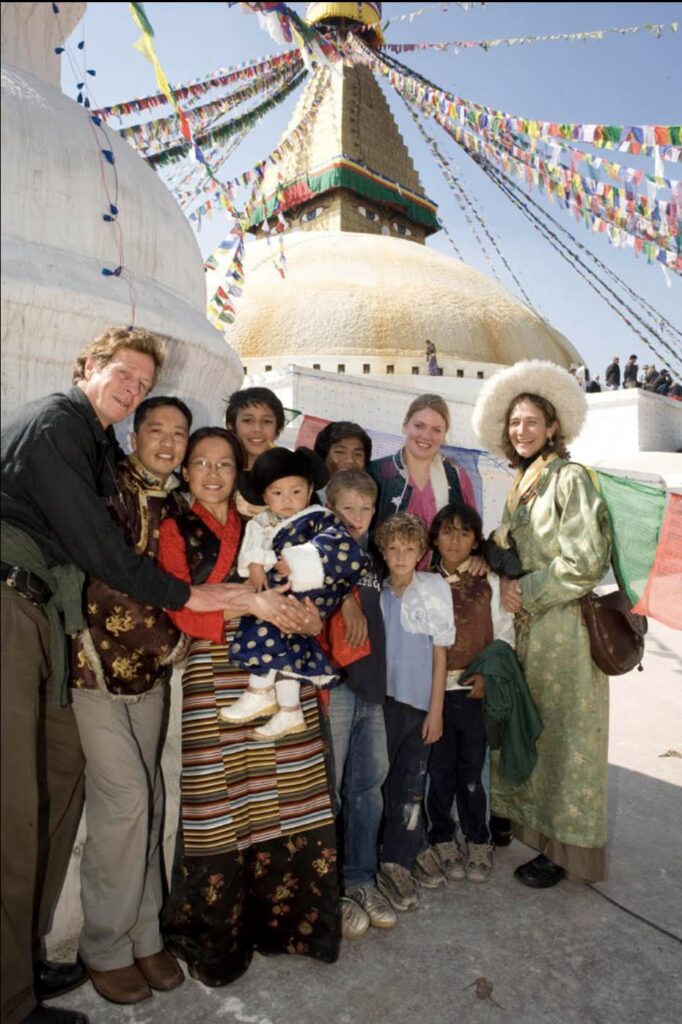

Family at Bodhanath Stupa

Carroll & husband Thomas Kelly

About Carroll Dunham:

Carroll is a medical anthropologist whose work explores human entanglement with other species, from microbes to yaks. Based in Nepal for 30 years, she has lived and traveled extensively amongst nomadic communities, including those in India, Mongolia, and China. A lifelong student of Buddhism, Tibetan medicine, and Himalayan medicinal plants, she is committed to amplifying Indigenous voices and advocating stewardship of fragile ecosystems. She is currently the co-founder of Around the World in 80 Fabrics. Revitalizing vanishing textile traditions to reduce petroleum-fueled fast fashion. A storyteller at heart, Carroll has authored five books and produced over a dozen documentaries for National Geographic, PBS, and BBC. As a Buddhist chaplain, she is passionate about resiliency and the human ability to thrive post disasters.

Around the World in 80 Fabrics

Rough Transcript (please excuse all errors)

[00:00:00] I am Olivia Clementine, and this is Love and Liberation. Today our guest is Carroll Dunham. Carroll is a medical anthropologist whose work explores human entanglement with other species, from microbes to yaks. Based in Nepal for 30 years, she has lived and traveled extensively amongst nomadic communities, including those in India, Mongolia, and China.

A lifelong student of Buddhism, Tibetan medicine, and Himalayan medicinal plants, she is committed to amplifying Indigenous voices and advocating stewardship of fragile ecosystems. She is currently the co founder of Around the World in 80 Fabrics. Revitalizing vanishing textile traditions to [00:01:00] reduce petroleum fueled fast fashion.

A storyteller at heart, Carroll has authored five books and produced over a dozen documentaries for National Geographic, PBS, and BBC. As a Buddhist chaplain, she is passionate about resiliency and the human ability to thrive post disasters.

Olivia: Let’s start by you landing in Nepal. So you lived in Nepal. You’re based there for 30 years. And what was the impetus to going there in the first place?

Carroll: Well, first, I always say for me, at least my life sort of, I was like, it was like Dorothy in Wizard of Oz.

I went from black and white into Technicolor when I first landed in Nepal. I. I was born and raised in in New Jersey [00:02:00] Exit A, Jersey girl. And I always wondered, I just was like, there’s gotta be other ways of living than this suburb life. You know, this, this narrative, this story plot, there’s, there’s gotta be more to living than this.

There’s gotta be other ways to be human. I was born and raised in, in New Jersey. Princeton, and then I went to the university, and I couldn’t wait to get out of the Ivy League, kind of very rather sort of stultifying, you know, very interesting intellectually, but not a lot of heart.

The neighbor, across the street was a little boy. I used to go under the fences and we’d play together with my best friend. And her older brother had just come back from Asia. And I was supposed to go to Sri Lanka and I was, I was very interested in college.

I was studying the anthropology of religion. I was very interested in engaged Buddhism. I was interested in how contemplation and activism, how did they communicate? What did that mean? How could [00:03:00] you social change without being angry at the same time, you know, just to be sitting still when the world is on fire.

So how could these poles of our being interfere? And so I was Very influenced by Joanna Macy’s work, and I was going to go to Sarvodaya in Sri Lanka, but then a war broke out. And so this best friend across the street, older brother said, Ah, you want to go to Nepal. You’re going to fall in love with this great guy named Tom Kelly.

And, and so he made sure I would go. He called up Tom’s mother and said, Hey, I have a friend who’s going to Nepal. Does Tom need anything? He was in Peace Corps. And she said, Yeah, I’m trying to get a camera to him. So she mails the camera to our neighbor. Our neighbor comes by, says, Can you take this over?

So, and at the time, so I was with a student at SIT, so I had to really fight hard at that time period. Princeton didn’t believe in time you know, [00:04:00] off or away. So I’m the next wave. In fact, I just had a whole bunch of Old friends who are the old 60s hippies, you know, been there you know, it was Christmas, Kathmandu 1966.

And they were showing all these pictures and I said, you know, I’m the next wave actually in the sociocultural history of Westerners in in Nepal, I’ve done great interviews with some of the early white -, Barbara Adams and Inger was married to the white Russian Boris Lisanovich and their stories of their first

moments coming to Katmandu, so we were the next wave and we were sort of like the nerdy student scholar types or the students who came were coming with school programs. There was a Pitzer program, there was the SIT as it was known, now it’s known as global learning. And so I came as a student instead of staying in a family stay.

They put me in a monastery, a nunnery. So my family was a Buddhist nunnery in [00:05:00] Swayambhu. And so that was really where my journey began. And I, I became fascinated by Westerners who became Tibetan Buddhist monks and nuns. And I said, I could be them and they could be me. And what is their story and who are they?

And I, I interviewed people like Mathieu Ricard and many other monks and nuns, Westerners who had had shaved their heads and it had entered the Vajrayana monastic path. And so I was supposed to go to study like women in development and I said, well, no, this is development. This is just inner development.

So that was when I first got there. And then. I bring this camera for this crazy guy named Tom Kelly who’d been there forever and eating rice and dal bhat and so he had been spending time up in Humla in far northwest Nepal. And he’d come on his, Big red Enfield motorcycle with his leather jacket and, and, and he dropped me off [00:06:00] and he did kind of expect like a peck on the cheek or that I’m like, no way, you know, there’s, there’s 20 nuns looking at you right now.

So he lured me up to an area in far Northwest Nepal called Humla. And he said, you know, he’d gotten a book contract and the writer wasn’t able to, to do it. And he said, you know, there are lots of nuns up there, so we ended up up there.

I didn’t know him that well. And It was make or break it when you spend a whole winter picking lice out of each other’s hair, and you’re hungry . We lived, we lived with a wonderful couple called Epi and Lobsang. They became like our grandparents. They lived in a cave in Yakpa.

And so he had come, he was originally a monk from Kham, from Eastern Tibet. He had studied in Gondon. So, and then when his teacher died, he was asked to marry the widow. And so they were on pilgrimage to Kailash [00:07:00] when the Cultural Revolution hit. And, and so they were then on their way down and the villagers of Yakba said, please, will you stay?

We have a terrible problem. There was high infant mortality in the area. And will you live in the cave where there, we believe this whole rock face is, is, you know, it’s harmful spirits. So we lived in the cave there. I’d have to tell my husband, don’t lean back against that pillar because it’s actually moving with cockroaches.

And, and then, and dear Epi, who was just the epitome of of compassion. She was really such a beautiful soul. She loved to put the old maggoty meat into the into the food. And we finally we said, you said, Abby, could we try it without it? And she said, But then it will have no flavor.

So and then that was the in 19 that was 1985. And we went down, we left Humla to go, we helped many [00:08:00] pilgrims were coming over the border illegally out from Tibet, because it was the Kalachakra of 1985 in Bodhgaya, and there was rumor at that time that that would be the very last Kalachakra His Holiness would give in this life.

Thank heavens that was not true. And that was a very profound experience for me. Very, very powerful experience. And so to see the rawness of the devotion of so many of the Tibetan pilgrims down there at that time. And I, I think that was when I initially took refuge and I went back and I tried to ask Jamgon Kongtrol was still alive and he was up in Woodstock and I was then working on my thesis at Princeton and I went up.

And he was in retreat and the people around said, he never sees anybody. He’s in retreat. I don’t know [00:09:00] why he’s saying yes to you because he shouldn’t because, but okay. And so I would, just go, can you teach me to meditate? I didn’t know what to ask or how to ask or what to do. So when I was in Nepal, Actually, as a student, then part of the time I spent, I lived with my Tibetan teacher from S.I.T, Sonam Thapgyal, and he had a house right in front of Shechen, and they were building Shechen. They were building the Shechen Monastery. And I was, I was, frankly, terrified of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche I can’t even begin to explain to you my experiences of being in his presence. Where you know, we say, use the word Kundun and we talk of His Holiness and things and for me the Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche had profound influence, but I, my mind would go blank.

All my intellectual [00:10:00] or defenses. It was a quality of being. So I, you know, I didn’t know how to ask the right questions or I, I just wanted to be in his presence. And he would come often to me in dreams, cause I think I was so scared to see him. And that, that that started my, my journey started my journey.

I was really blessed. Nepal is such a cauldron of extraordinary beings. You know, if you think of it almost like molecules banging against each other, I think you would have to be half dead not to you know, to encounter the dharma in the Kathmandu Valley. And it’s a great soup.

And Bhakha Tulku was a very, very important. And still is for me. I love him with all my heart and he really taught. me how to ground practice in everyday living. I learned my Dakini practices. I learned [00:11:00] sang from him and he, he’s so humble and has no ego.

And, he’s an artist and, and and it was a renegade and a little bit of a rebel within the traditional orthodoxy. And so I love that and a great scholar and and his kindness was immense. And I was very close with his daughter as well. Yeshe, and we, I traveled with her and Ian Baker.

We traveled throughout Tibet together. And so when Ian and I were working on a book together. And we went up to see Mindrolling Rinpoche, and that for me was very powerful. So at that time, Khandro Rinpoche was, she was the translator. She hadn’t, wasn’t wearing robes yet, still had her hair. And I remember for me, that was a really important in my little journey.

Everyone has, we all have our journeys, we all have our stories, but because, you I don’t know for you, maybe you have this experience, or maybe someone who’s listening, I just remember, okay, [00:12:00] there was like, like a white fog with light almost penetrating through it.

And then it was suddenly like, I could think and there were thoughts and I was a little kid and I’m crawling, you know, on the ground, and I’m like, and I’m sort of like, and, and so Mindroling Rinpoche, Was the first person I, I never had shared that I was, it was something that I, I, I used to feel sadness as I was growing up as a child and thinking I’m getting further away from that and I need to go back.

I need to find that. What, what is that all about? And Rinpoche said, well, listen, you don’t live here. You’ve got to find Trulshik Rinpoche and you need, you need to, you know, receive clear light, some clear light teachings from him. So I, then it was like a great odyssey. I’m sure that I, and I’m quite sure from my life and my obstacles and challenges, I always joke.

I think I must’ve been a really. Badass, Khampa, [00:13:00] bandido, must have done bad, nasty things in my last life. I don’t know. I really don’t know. But I would go up to, to Solo and he would have just left. We kept missing each other for a long time.

Finally, I meet with him and he’s like, well, I need the text. So it took me many, many years to be able to receive those teachings and for which I am grateful. You know, forever, forever, forever grateful. And yeah, Trulshik Rinpoche is a very important light in my heart and in my trail and my path.

We met at Lama Wangdu cremation and Lama Wangdu came into my life when I was kind of broken. Probably always was broken, but I was really broken. I had had, I was working with, you know, we always say never do business with friends, but I never got that memo. And there was a lot of betrayals and a lot of, you know, broken trusts.[00:14:00]

So I was having a hard time, you know, being able to trust my own even ability to evaluate who I should trust and shouldn’t trust. And, Lama Wangdu taught me fearlessness. He got me back up on my feet. You know, he taught me the fearlessness, fearlessness of generosity. I find tragically in the West, how capitalism influences Dharma in a terrible way.

And so we would do, yeah, amazing practices, you know, with that. Rinpoche and, you know, and Pashupatinath and some of the great sacred sites of Kathmandu.

Olivia: And what was it in particular that he taught around generosity?

Carroll: Well, so because his practice is Chöd, and Chöd is the practice of cutting through fear but what, was so special about Lama Wangdu was, .

To give you two stories and I’ll get to your question. [00:15:00] So I once was doing a film, there was these French filmmakers, they had a philosophical orientation. They wanted to kind of, Put everything into their box. They already had rather than sort of seeing what was there. So we had gone to see many, many great and filmed many, many great llamas.

And it was near the end. And I was like, I really think you should come in. We see meet Lama Wangdu and they were like, This is all the ritual. This is all the folk religion. This is nothing to do with, you know, the coercion and the, you know, we want the big teachings. So, we came, Rinpoche was deep in Chöd, and if anyone here has never heard Chöd, it’s different than many of of the other monastic teachings.

It’s very melodic. You know, it’s, it’s traditionally more often householders, even though many, many monastic [00:16:00] communities will also practice. Chöd comes from Indian charnel ground traditions originally. So he was deep in with the drums and there’s lots of ritual drama and it’s powerful energetically.

And so he was kind enough because he had, I had requested and he’s so generous. He made the time. So in the break, the filmmakers came up and he immediately, like he could see immediately, which was just like Lama Wangdu. I’ve never met someone quite so he could see what you were thinking.

I remember once I like looked up, I was like, wow, that’s a really beautiful Vajrapani statue. He goes, oh, I hadn’t even said anything. Okay. Okay. I’m not, no desire. I’m going to just only look at it.

Any desire he will pick up. So he immediately, Went straight into a very, very profound teaching about the kata and if it’s white and pristine, but if it’s in, [00:17:00] you know, you put it in the ash box.

So in other words, what it’s surrounded with and yet what will stay pristine and pure. And he gave such an extraordinary Dzogchen teaching. They, they were just, their jaws were dropped. And it was only like an hour. They said, but wait, can we, can we go back? I’m like, Sorry, you missed it. You know, you either say that’s the way it works, you either are there or you’re not.

He taught generosity through his being. I’ve never, if you ever Ever did ritual with with Rinpoche, you know, he is gusto, he was like this big laughing belly with, you know, and he needed big hugs, warm hugs, but he, he would just like, grab the offerings, not like little and sweet and delicate, but it was, more and more.

And yeah, I honestly have never met A more generous being. I mean, he, he, he really [00:18:00] was not attached and he was the great distributor. So it was always great because you knew if you made an offering to him, he would just give it all away. So you were always having to think so creatively of how can I offer something that I know will just be disseminated into the universe.

Olivia: Oh, I love that so much. I, there’s, there’s a lot of things you’ve shared. Can we go back into everything pretty much? So maybe we’ll just stick in the, in the realm of Buddhism right now.

Cause there’s so many interesting meetings that you’ve had. So maybe we could start with Jamgon Kongtrol. So you met him then in New York and was he the person you took refuge with.

Carroll: I didn’t take refuge with him.

So I actually sort of technically, ritually at the Kalachakra in 1985 is when I formerly took refuge, so it would have been with His Holiness, Dalai Lama, and I, I have one sweet little Dalai Lama [00:19:00] story because with His Holiness so when with Ian Baker, we were working on a book with my husband on life cycles of Tibet.

This is many years ago. And so we go and we interviewed him and he was very interested in what was going on with the politics in Nepal. And, you know, he wanted to know all about the emerging of the Maoist situation there, et cetera. But you know, and I was, I was sort of trying to fish for quotes.

And I’m like, isn’t, isn’t sort of everyone our teacher and, and everyone, you know, cause we’re all Buddhas. And so shouldn’t we see everyone as our teacher, is that great, great American and egalitarian and seeing, what we can learn from each other.

And I loved it cause he’d been all very sweet and nice, and he suddenly went, he looked over at me and I felt like he was like talking to, like, inside, and he goes, like, like, this is not for everybody else, but it’s like, for you, [00:20:00] not everyone is your teacher.

And I really am grateful because that’s a, very, very beautiful and powerful teaching and took me many years with to learn discernment and you know, learn to really keep the focus with one, with one’s teachers. So I’m very, very grateful for that lesson from. His holiness.

I had the blessing to be at Khyentse Rinpoche’s cremation in Bhutan. And that was a very powerful and extraordinary event. And I have to just tell this story. I will get back, but this, it’s too funny. It’s too amazing. This is too amazing. I was just in Bhutan. three weeks ago, and I’m walking up this trail. Okay. I have had the blessing. I have think I have been able to do the pilgrimage up to Taksang. Somebody asked me maybe at about 45 times, [00:21:00] 46 times. I think I’m really blessed. And each time it’s like, I’m, I’m indescribably happy and delighted. I, I feel such a blessing.

So on my very first time I ever walked up there was Right after Khyentse, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche’s cremation, and of course we had rainbows around the sun, and you had to start way, way back in those days. It was a long walk up. There was a sweet little mild mannered, a monk, and he accompanied us. He became kind of like our Little pilgrim, you know, weird pilgrims on the trail.

And we went up together and then we went, came back and we shared a taxi. And, and then as we got out and he was so sweet and humble, he, he handed us his card , and we saw that it was the , Nechung Oracle . We were like, oh my gosh. He was so sweet. So, okay. Take the tape forward. You know, we’re, we’re at whatever, almost 30 years later or whatever.

And I see these [00:22:00] Mongolian monks ahead. And so I’ve spent over 20 summers in Mongolia. And so I go up and using my poor Mongolian and I’m so happy because I’ve never seen Mongolian monks on the trail to talk some they said no But you really need to meet our teacher. He’s fresh from Dharamsala.

I said, oh, that’s nice So I went switched to Tibetan. We had a beautiful conversation. He seemed like a beautiful soul up the trail. My friend says, but don’t you know, that’s the Nechung Oracle. I said, what? So on the way down, I said, Rinpoche, did you walk up this trail, right? Were you here for Khyentse Rinpoche’s cremation?

So the beauty or the power of that, of that trail is so, so precious. So I always say I had to wait 25 years for my teacher to come back and ripen in the form of Yangse Rinpoche.

Sean Price is an amazing monk and [00:23:00] an incredible translator and he helped to translate all of Khyentse Rinpoche’s terma teachings. Rabjam Rinpoche really gave the foundation. I would say like filling in any of the cracks while I was raising children in my householder yogic way.

So I joined with the Sangha and we together fulfilled those practices. We would go every year to Bodhgaya for over 10 years and received the full cycle of Rinpoche’s terma teachings. And so I’m very grateful to Chokling Rinpoche and Rabjam Rinpoche for for Really filling those gaps and giving license for outrageous behavior.

When you’re as old as me, you go, I could have used, maybe I, maybe I’ve been outrageous without license before, or now that I’m so old, I sometimes want to go to bed. Maybe [00:24:00] I don’t want to be outrageous anymore.

I mean, we remember when Rabjam Rinpoche was a young teenager and you know, there was a lot on his shoulders to be able to carry the lineage and he’s, he’s done that with such extraordinary grace and, and purpose. He’s about to give amazing, huge teachings, Rinchen Terzod, all in Bhutan.

And for the Yangsi Rinpoche, you know, he’s coming at it from a different place I feel like the young Kalu Rinpoche as well. I’m so grateful to them that I think some of the things, at least I’m just saying as a Westerner who’s lived in Asia and lived in Nepal for 34 years and as a mother.

So as a mother, there’s something about tradition, but there is also something about innovation and the challenges in the monastic worlds and some monastic situations can be like really bad British boarding schools the abuse that can [00:25:00] happen.

I mean, I was amazed. I just led a national geographic trip and the Bhutanese guides, For the first time, they were saying, the guides were saying, you know, we’ve had sexual abuse problems in our monasteries, we’re now trying to work with them, but the fact that they’re even talking about it, and that’s what they’re telling, like, tourists who don’t even know that there were problems or have been problems or things like that.

So I am really excited about the next generation, this real complexity of keeping the dharma not brittle and dry and desiccated, but juicy and alive and vibrant and meaningful in our times. So,

Olivia: Yeah, I so appreciate hearing that. And Trukshik Rinpoche, so tell me about your experience with him.

Carroll: Well, I’m going to just tell you this simple story. Some people, their relationship with the Dharma will be purely intellectual.

For others, it would maybe emotional. [00:26:00] So for me, I remember when I was young, I used to cry. I’d go like, I’m never going to find a teacher. I’m going to be locked down. How do I know if I have found it? The teachers do, they find, they find us, and then, and if you let your body, your body will tell you or know you, so, like, my experiences of Trukshik Rinpoche, similar to Khyentse, were just pure presence, like, I just have such great memories of being up in Thubten Choling and I remember him telling and crying with me, telling his story of his escape out of Tibet.

I mean, he was so lucky he, well, so he had first of all, just re built all of his monastery in Tibet in Rongbo. And if he had been at his residence, he was up checking on the tsetsampas. These are lifelong retreatants that were all up in the glacier just at the base of Mount [00:27:00] Everest and Chomolungma.

And so he was checking on them when the word came that the Chinese were here and he had to leave. So he went right over the Nangpa La into Khumbu, he didn’t, couldn’t even go back to his home, pick up his bag, anything. We did a film and included him in it and we went up to a place where when he came into out of exile, he went on, three year retreat and it’s a sacred lake that’s just above north of Day’s Walk above Thubten Choling. And so the, there was a nun who told me this powerful story that she was his attendant during the his time he was doing that retreat and that a vulture came flying out. It was evening time, came flying out.

And circled them three times, and that it had a tear in its eye, and it spoke to [00:28:00] them. I’m just telling you the story, you can make of it what you like. And he said that, the vulture said, I’m your teacher, I’m Dzatrul Rinpoche. And I’m so sorry you’ve suffered so much. It’s been hard, you know, with exile, coming from, from Tibet, all that you’ve suffered.

Why don’t you come with me to Copper Mountain Paradise? And Rinpoche took a breath. He said, No, I think I have work to do here in Solo. I will come. I think these people, I can, I can leave some seeds of Dharma here. I will come later. And then the bird circled three times and went back. And then one of my great memories of the Trulkshik Rinpoche is This is a funny one.

We were in this helicopter, this [00:29:00] big old Russian helicopter, and, and the attendants come, and they put the tiger skin down for him, and it’s, and you know, the sound’s going really noisy. Rinpoche turns to me, and he goes, I can’t hear, but it’s like, so his attendant whispers to me, he says, yes, in the old days, we Buddhas used to fly. Now we just take helicopters. And he, then he had this huge bag of tsampa mixed with grains and he would, he made prayers and he blew on them and they opened the door and winds coming in and we went way down low and all the villages. And all the villagers would come out and they would put their hands up in the sky because it was like raining barley, like, you know, the, the blessings, you know, so, so Rinpoche was using the technology to spread the blessings all over and through the [00:30:00] land.

And then I remember once going up for Mani Rimdu and I just wanted to get my prayer flags blessed to put them up early. And it was early in the morning, maybe 6. 30, 7 in the morning. And I just pulled the curtain a little bit. And there he was. He was in his 80s, by then. And he was just simply doing his prostrations.

And it was, it was so beautiful. Even Buddhas do prostrations. So that humility practice is unceasing. And that was an embodiment of a great teaching.

Olivia: In terms of language. So. What Himalayan languages have you taken up and how did you learn those?

Because it sounds like you are, you know, communicating with some of these teachers or people you run into.

Carroll: I studied Tibetan. And people will joke and laugh because I sound like a nomad or a [00:31:00] Dropa. I speak like a local, let’s put it that way, that way. So I don’t have a high, high language. I have. You know, the, the language, the simple folks,

Olivia: What area do you think you’ve taken up Tibetan from? What nomadic area?

Carroll: The dialect that’s spoken in the Humla region, for example, which is influenced by Western Tibetan.

So like, you know, Central Tibetan, we say Dikarire, then they say Idichidakpa, you know, it’s like, you know, it’s just different. But so you have sort of along the high spine of the Himalayas with you know, through Mustang These, these high mountain areas. And I, I would really love to study. I mean, like I think of Francois Pomare and we have friends who are, you know, just exquisite Dzongkha speakers or – in you know, in Bhutan.

But my [00:32:00] Bhutanese is not very good because I get lazy because I speak Nepalese and I’m very grateful. I really love and enjoy speaking Nepali. It’s a very joyous, playful language actually. And because we have so many, 76 different ethnic groups in Nepal.

And so it’s a second language for everybody. It’s not like, you have to speak pure Parisian French or, we won’t listen to you. You know, everybody’s trying to muddle along and people are very open and understanding and, you know, they care more about communicating than perfect grammar.

So

Olivia: definitely. Did you learn Nepali from living there all those years, just picking it up naturally? I

Carroll: did. I never, I never I studied it formally, and in my old age, I want to study Sanskrit. That’s what I need to start on. I’m Mongolian and Sanskrit, I’ve got to work on.

Olivia: Wow. Exciting. A lot, a

Carroll: lot, a lot to work on.

Olivia: Yeah. I’m sure you’ll learn it quite quickly. You’re so studious over there. [00:33:00]

Carroll: I think I’m one of those people that I’m a poster child. If, if, Carroll can learn a language anybody can learn. I’m not a natural language learner. And I, I mean, in Mongolian, they just laugh hysterically because they’ll go, and I’ll go.

I like , what I, what I hear, and then what comes out my mouth. Some people who are great musicians and you know, they have beautiful ears and they really have a, you know, I have like a friend Charles Ramble and he’s just exquisite with so many of the subtle dialects in the of Himalayan dialects or Mark Turin.

He’s an amazing linguist out of the Himalayas. And yeah, there are folks that really. are just savants in the languages. I’m definitely not one of those.

Olivia: But it’s also nice that you speak the casual tongue as well, and that you at least have a way to be able to connect, which is most important as well.

I’m wondering, yeah, [00:34:00] as we can, as we go back to the guy on the motorcycle that you spent some time with up in Humla. How long were you in Humla first, living in the cave?

Carroll: Yeah, that, that was from I think we went up in October. We came down in April and that was the first time. But we went out in January for the Kala Chakra and then came back.

We did a book on the, on the cycle of the seasons in Humla. So we spent a whole year altogether up in that region and, and with those communities, you know, we have friendships now that, you know, are generations that tell the stories.

I’m an auntie to a good friend, Tenzin Doma. I hope she’s going to write the most extraordinary grand epic, which it should be, because the history and the stories of there are, are. It’s an [00:35:00] extraordinary part of the Himalayas, extraordinary and, and complex. So it used to be a part of the Zhangjun Kingdom.

So Bon, very strong, but you would have a lot of different Lamas coming down. It’s a fascinating history of then of of Bon and Buddhism and shamanism and the Hinduism that they practice up there. I don’t think Orthodox Hindus would even, you know, recognize either really fascinating.

And then, you know, like, so the Hindus even there will worship you know, traditionally honored. Padmasambhava, they called him up there, the Wali Kali Lama. You know, so very interesting area, very complex.

Olivia: And is that the area where you were studying polyandry? Mm hmm.

Carroll: I was studying polyandry that’s over 30 years ago and in those time periods in the Nyimba communities, the majority of people were practicing polyandry the Maoist revolution and economic [00:36:00] shifts, barely anyone is practicing anymore and that has to do with economic abundance, which is a good thing.

But there you would find, you know, in Mugu, in Dolpo, in Mustang. Sometimes, you know, they’re in the early days, there used to be amongst the Sherpa. Again, when the potato came in the 1920s, you know, they became a wealthier and less of that. But yeah, the polyandry, very interesting looking at, you know, relationships and how we structure relationships and what’s okay for the Nyimba, for example, you know, brothers never fight.

You know, it was one of the rule ideals. I mean, of course, brothers fight, we have ideals to we say in our country here, you know, thou shalt not kill. But fortunately, our murder rates are still doesn’t seem to, you know, hit upon it. So the ideal and the real but the notion of how do you, you [00:37:00] know, share your most precious object.

There’s less kids because there’s only one woman that can be pregnant at the time. And then all the males, are contributing. It was a tripartite economy. So one would be up in Tibet, you know with trading perhaps.

And then one would be with the animals down south or with on the salt wool trades, one would be home. And then the most challenging times would be in the harvest time, because everyone would have to come home to help with harvest. And that was usually wedding season as well. So you see things shift and things change and relationships shift and relationships change.

We did an interesting film with the BBC called the Dragon Bride and we try to have her helped tell her story of what it means from a woman’s perspective to know that you’re going to be marrying all these brothers.

And what kind of future will you have? Because traditionally a dragon, a [00:38:00] woman born in the dragon, everybody would want to marry because that means that she would have the norbus. She would bring wealth and prosperity. They’re known for their hospitality and their graciousness and a lot of qualities that they look for traditionally in a woman and the Maoist time period in Humla was a complex one because , if you’re only having one woman with four brothers, that means then you have a lot of women that aren’t getting married. And so they would stay in their brother’s homes and as labor sometimes have a honey or a lover elsewhere.

And, and it was interesting because up in further North, Limi, Halji, – those areas. If a child was born out of wedlock from a lover or whatever, that’s great. That’s just another member of the family that can help. But then as you move further south with the Sanskritization Hinduization of the culture it was not okay to have a child out of wedlock.

And so I was learning from the women. I’d [00:39:00] go out and help them carry the manure on my backs and help them in the fields. And, and I, there, there’s a lot of different ways for of herbs and other methods that were used for abortion techniques. And that was when I started to become very interested in herbs and in medicinal plants, particularly it was through women’s reproductive.

And they all wanted to know, they were like, wait a second, you’re how old? And you don’t have any kids? What do you know? And I’d be like, look, I can take you down to the local health, you know, clinic. We go together. It’s the same thing. They’re like, oh, that’s too complicated. And you have to remember, like they would often like share the pills or you start to realize how complicated

reproductive health care is and very tragic in the Humla region we go up with medical expeditions with Roshi Joan Halifax and and we would find like in areas like that. It’s it’s so tragic because you know, people be like, well, nobody’s going to be here [00:40:00] again for another how many years. So they would give like Deprovera.

We’d find women with like, you know Six implants. I have pictures and you know, and you can imagine how they felt with all that hormone mix up in their bodies really tough.

Olivia: Yeah. Yeah. I can only imagine. So you’re, so you’re walking around with them, learning about their stories at the time you’re just arriving in Nepal, right?

So like, how are you communicating with them? How is that working?

Carroll: Oh my gosh. Frustrating.

I had studied Tibetan , down in Kathmandu while I was living in the nunnery. And then I’m up in Humla and I’m having a really hard time with their language, right? Cause it’s a dialect at first, really hard time.

And I’m asking millions of questions of my husband. I’m driving my husband. Absolutely. Gonzo

we get snowed in. So we were stuck up there. Like I [00:41:00] remember one time I got really angry. I’m like, that’s it.

I’m leaving. And then he looks at me and he laughs. He’s like, good luck, honey. It’s like, it’s going to take you three months to walk over those bales. Aside the fact that they’re covered. Good luck. So, yeah, we we kind of had to make it work. And so we’ve been making it work for over 40 years.

Olivia: Yeah, will you actually speak about that because both of your adventurous souls found each other.

And what would you, like, what would you say are some of the qualities you both nurture in your relationship to allow it to thrive all of these years?

Carroll: Well, I mean, Thomas is an artist. You know, and he’s a photographer is a very sweet and sensitive soul, and and he loves yoga.

He’s a pranayama practitioner and we both absolutely Love the Himalayas. We, [00:42:00] well, we love Mongolia too. And yeah, we love wilderness. We love exploring. And, and, and my husband is really like, I always joke. I would never know my husband as well. If I didn’t know Nepalese, because he came over doing Peace Corps and he just blossomed,

He’s a different personality when he speaks Nepali than when he speaks English. He really is. He really is. He’s much more playful when he speaks Nepali. He’s much more playful. He’s much more silly. It’s really funny. It’s really fun.

Olivia: Do you speak Nepali to each other ever or always? Well,

Carroll: so, well, the only thing is and sometimes even as a whole family with my kids too, but we early, we were just like, no, no, you can only speak You know, mother tongue, mother, they, they say with children, they say, no, they’ll get it from everybody else.

So we would have to work really hard. Cause when Nepali [00:43:00] can be like the language of love, like when you have a little baby, you just, we’d have to like cut yourself

Olivia: off.

Carroll: Yeah. Easy.

For sure.

Olivia: So you arrive in Humla, you spend many months there, minus the Kala Chakra, you go down maybe for a month. Is that how long Kala Chakra was? Yeah. Then you come back up and then you finish this kind of seasonal time together. So Between that to getting married. When was that? How long?

Carroll: Seven years, seven years, you know, that sacred mystic number seven, seven steps to Buddhahood. And there’s, but yeah, we, we lived together for seven years. So after seven years, you kind of know if you want to be together or you don’t want to be together and, you know, there are faults and foibles. So we decided, to get married because I think also we were thinking maybe about having kids or [00:44:00] something like that.

And and also, we loved our projects and being out there and, and, and I didn’t mention, we also raised six foster children before we had our own kids. So and that was not a plan. I don’t think we’re very good planners. And so they were all kids who came from difficult circumstances up in high Himalayan mountain regions from Humla, from -, and from Pema Bhuti is, is from the Kumbu, Solukumbu area, but her father had died in a avalanche on on Annapurna. So they all had either their, you know, one, Parent that was missing and there were a lot of mouths to feed and in all situations, none of them we sought out, none of them we weren’t looking for, we weren’t looking to, to adopt.

We were, people would say, Granny, can you, [00:45:00] you know, take care of our kids? And, and, and we were so naive because we kind of thought, Oh, well, yeah, we can, you know, sponsor them at school and education. Yeah, we’re happy to do that. But I think in the family’s minds. It was like, okay, they’re yours now. My parenting skills were all upside down.

I

Olivia: mean, cause you’re, you’re in your twenties, right? Is that right? Yeah.

Carroll: Yeah. And we had situations with, you know, unwanted pregnancy before I knew how to change diapers, you know, like, I mean, it was complicated.

Olivia: And were they all living with you?

No, they went to Mount Kailash boarding school.

Carroll: And Pema started at Sri Mandip at, at Thrangu Rinpoche’s, then went to Mount Kailash and they would, so they would come home for the holidays and the weekends and things like that. I’m so excited because my granddaughter, Tsaring I think is coming and she may be going to college and living with us here [00:46:00] now.

So I

Olivia: actually, I saw Pema right before I left and she was telling me about all of this. So it’s so exciting. Yeah. I mean, I, I wonder too, like for the lifestyle that you and and your husband have, if it’s possible to plan something like that. I don’t think like bigness comes from planning and like you, you, you’re living in like such an outside of the edges, like that’s literally how you’re living, right.

You’re exploring in between places. I just don’t know if it’s possible to be a planner in the realm.

Carroll: Is it? Yeah, it’s no, I think you’re, we so wanted to live in the moment in the presence and, and, and you know that, you know what it’s like to be in Nepal and that intoxicating presentness that is so spectacular, like life can be really rich and full and engaging and interactive entanglement, right?

I mean. You know, there’s a lot of people, it’s a lot of density, and there’s a lot of story, and it’s all [00:47:00] happening. You know, it’s, it’s never a dull moment, that’s for sure. You know, there’s all the ingredients for living a rich life at the same time. Extraordinary pathos, extraordinary suffering and in such intense levels that, it’s, you know, painful.

After I did some years helping work with medical expeditions in the mountains. I, I worked for some time in the burn unit at Bir hospital and it was challenging, really, really tough. I mean, you see there women who were the families have. tried to light them on fire with their synthetic saris because the family’s not giving another motorcycle or refrigerator, you know, for the dowry.

And and with 1930s level medical care. And yet some of the most [00:48:00] exquisitely compassionate, beautiful people I ever met were the workers in the burn unit. And it’s so challenging because sometimes there’s nowhere for the women to go. So, you know, not only we, we had, we need to try to raise money just for the bandages, just for taking care of them.

But so many of them, You know, didn’t even have the rupees to the bus fare to get home. And then sometimes they have to go back into the very places where horrible, horrible things had happened. So you know, Bardo, the notions of Bardo or suffering or yeah, they’re real. They’re not in other realms.

You can also experience them in this world and in this realm.

Olivia: Yeah. Yeah. It’s so true. They’re just like that extreme suffering and then being also in a country that’s so apparently sacred, like everything sacred is also shared, right? Everywhere you go, you have that sense. And [00:49:00] yet kind of the inner being kind of grappling with both of those is a lot to, to find.

I think that’s the

Carroll: best thing about Nepal is that the brain can’t grasp it because It’s so intoxicating, isn’t it? It’s like the good, the bad and the ugly, you know, you take them within and there’s incense and shit at the same time. Sounds are like there’s bells and then there’s, you know, bad rap or whatever, you know, you, You know, if you want to dissolve dualism, it’s a great place to do that.

Olivia: It’s so true. So true. And I mean, also you were there pre market economy. Were there places that you lived where you were living on, I guess, probably Humla, like farming, wild gathering, bartering.

I imagine like up there in the mountains, you [00:50:00] were sustained on that. What was your experience of that? And then what was the experience witnessing everyone around you living in that time?

Carroll: Wow. You know, the, the, The introduction of market economy. That’s a, it’s a huge one into Nepal. Well, I mean, first of all, to be honest, like my experiences in Humla, I mean, I remember being hungry.

I mean, we were hungry. We were really hungry. Hungry a lot. And I remember there was a year there was a virus so that the bees and they, and a Japanese man had climbed a mountain. So they, they were sure that that had caused, that was the virus that had killed the bees. So there was no honey, there was no sweet.

But the, the deficit was, was real you know, the, the, the, the change though, in relationships with market economy to Nepal, or, or, or, or. Enormous, because before that, and I will [00:51:00] speak now of also in Kathmandu Valley and times living there as well people really needed each other. I mean, reciprocity is an obligation.

And so obligation is through gift it. So the gift giving. You know, so you do that so that you will be okay when times are difficult or whatever, and you can get the return because the relationships have been made. So to see the market economy come is, has been exquisitely painful, and I, I would say not just for me, but any Nepalese Tibetan of my age, I think, I don’t think some of us will even talk about or remember the old days kind of thing.

But And in terms of also just the ecology and the of, you know, of the whole entire valley, you know, Talajou’s womb, a very sacred place that now, you know, it’s like has almost a venereal disease of You know, the rivers of, of the Kathmandu Valley [00:52:00] that I, I knew them when they were clean. And that’s no, no longer the case, but to see the shift in relationship especially like, you know, you, so we have a, it’s a migrant labor population.

So mostly remittance economy in early days, people would send money home. And, you know, because that’s because we all are linked because that’s family and to belong to the family and then some of them realized, you know what, maybe I don’t have to send the money home and also the tragedy of, you know, the families don’t understand they don’t know how hard it is when you’re, when you’re Working in the Middle East and being treated lower than a slave you know, your sense of self and who you are and the confusion and the pain of all that.

I mean, I, the market economy has been very painful and brutal to families and family structure in Nepal and across the board, you know, impacted and influenced. So the breakups you [00:53:00] have in a lot of villages where you’ll, You know, the, there’s a grandma taking care of a child because young couple’s married and then the guy goes off to try to get money and then he disappears and then the mom maybe has an affair with somebody and then runs off and then who’s going to take care of the kid and so there’s, you know there’s a lot of social issues that have occurred from this older way, the giving way, the giving and receiving way and understanding that and the flow To suddenly going, how much, and seeing, yeah, the, the ostentatious display and, and the consumerism, the explosion of consumerism.

Olivia: Yeah. Unfortunately. Yeah, I mean, I can’t imagine to from your perspective because you’ve seen it in such a dramatic shift, like sometimes there’s a gradual shift, right? And maybe it’s never really been fully intact in a long time that pre economy, pre market economy But you’ve seen it in your lifetime and in the Kathmandu Valley.

It [00:54:00] is so extreme. Being up in some villages, the common story I hear is, Oh, my children are now in Kathmandu. They’re getting education. I don’t know if they’ll ever come back or they’re going to another country. And then you ask about agriculture, the beautiful barley fields around and you ask, well, will this continue?

And they’re like, Oh, I don’t know. And then everyone’s waiting for the next parcel from Kathmandu to bring their dresses or their belongings and all that, that closed cycle of self sustenance is no longer there. And it’s very, very heartbreaking to see that. And I’m wondering just from your experience, You know, the Himalayas in and out.

Are there places that are untouched or is just every place impacted,

Carroll: you know pretty much everywhere. You know, you’re going to find folks that have You know, relatives that are in the city or have gone to the tri or, I mean, you can go to, you know, remote parts of Mugu and remote parts of Humla.

There are communities that have less links than others, but with [00:55:00] technologies and communication that have also come through, I mean, I remember little things like, so when I first came to Nepal, wasn’t a lot of furniture. Yeah. So when you go to most people’s house, you’d sit on a suko, you’d sit on the mat and you know, there, there, there might be a little tiny stool, but that was about it.

And so I remember like suddenly, like all the furniture stores, it’s like, Oh my gosh, that was a little marker. Then I remember Bapatini, they would, there was mannequins and then they had, they had on their pants and I’m like, Oh, that’s that’s a marker because when we first came here, we were all taught we had to cover ourselves because, you know, it’s so interesting when you think of the body and different erogenous zones.

So, you know, like if I put this way, way down here and show a little cleavage, that’s not a problem. And in our culture, to show your belly like in a bikini, that was. pretty [00:56:00] radical in the 60s, but you know, obviously with a sari, that’s no problem, but don’t show your ankle, right?

You know, so which parts of a woman’s body, you know, were to be covered. So like, you know, nowadays you go to a wedding and it’s like, you’ll have a grandma will be in her sari and then a middle aged mom will be in their kurta. And then, and then the young daughter sometimes will be in clothes so sexy and naughty that even in the West, we would go, don’t think you should wear that out tonight. But to them, it’s like, well, she’s being modern. But as an anthropologist, part of me is slightly concerned only just because what I see, I’m just talking about market economy with women, at least, is that commodification of women is you, There’s not a lot of freedom there.

Like actually, if we’re looking at that, that evolution and even in clothing, because then the young little girl that’s being sexualized, like [00:57:00] that’s not necessarily freedom. So I worry about that. Yeah. That makes that that’s, that’s come in with them, all the market stuff and all of those things. And another thing, now, when you go to Nepal, the tragedy is, like at our home, we have a family we live with and, Sita only was able to go to school to fifth grade.

So education is super important. The kids are doing really well. But the thing is, they’d have no sense of social media. So to them it’s sort of like being modern, but the kids are like, they’re on the computer or they’re on their phone.

Like that’s, that’s a sign symbol of modernity, but they have no idea of the content, and they’d have no idea of the toxicity, and they have no idea of the suffering that’s going on within that. So, you know, the hijacking of nervous system. We just need to connect connect the kids with nature that’s what we have to do.

Olivia: I want to get into that with your children. So you [00:58:00] raised your children between it sounded like many different countries like Mongolia, Nepal, maybe India. Will you just talk about raising your kids in Nepal and like what ages were they being raised there?

Carroll: So I would, I used to joke that we were just like sheep that grazed and we just had the rotating pastures, you know, when we, we would just rotate different seasons, different times of the year. Cause the, the thing with children is, is they really do need that stability. And Nepal. And Kathmandu was always the home and the base.

My oldest son was born at home in Kathmandu, in Talajus Valley. He has a mark on his, on his foot. He was the blessing of the Devi is with him. And I really want to make sure that the four yogini protectors, he would really have that, that, that blessing and that link and connection. And my younger son was born because he happened, [00:59:00] he happened, his due date, he was, he, we was, was the day after Christmas.

So we have a home in Goa and Indian on the coast because we used to always spend our falls and our springs up in the mountains and we needed to thaw out a little bit. So we would in the winter go down and we would do a lot of yoga and and let the sound of the ocean kind of do its magic on us.

So in the summer times. Monsoon is, you know, wonderful and magical, but sometimes then you start to get moldy and soggy too, so we had some very close friends and Enkay is Mongolian and married to Christoph and their children were the same age as our children and they kept saying, come on up, ride horses, we have gers.

Come join us. And so that was like the [01:00:00] steps were profound place of healing. For me personally, I had, as I say, I’d been this hard time with obstacles, working with with friends and like sort of crawled up to Mongolia. And Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. I, I’d had bad experiences on horses in Zanskar with a good friend, Kim Gutz Chow.

She’s a wonderful anthropologist, has done a lot of interesting work on nuns. And I did a lot of interesting work. She was doing nuns, witches, and oracles. So I came in and I would, she’d have me ask all the difficult questions about witches, because we’ve had a lot of witches in Humla. And if you talk too much about witches, witches hear you, and then they’ll come.

I could tell you witches stories to you.

Olivia: I would love to hear which is

Carroll: purple in the face. And yeah, really, I had to have really good, some interesting stories on interpretation. So I, I had fallen really badly because, you know, all different horses had different language. And so I thought that by, you know, pulling like that, I was making it stop, but in.[01:01:00]

Their language that is in go at full speed gallop. So I fell really on the hard. And so I said never riding again. And so up in Mongolia, big storm coming in, everybody else has gotten in the van. I love medicinal plants. So I was lost with the plants on while I was on my horse. Mongolian rider comes in and out, which means you dumb idiot, you were supposed to.

So we’re going and he takes the whip. And when you’re at the 40 horses going at full gallop. You have to surrender, you have to let go. And so I went through fear to the other side. I mean, it was a really powerful experience and I sort of. fell off the horse and was never the same again.

And so the horses are profound teachers for me, very profound that deep relationship and working with them. Horses know us better than we know ourselves. And so I’m so grateful. They, what Mongolia, we would go in the summers [01:02:00] and the boys, they started it too. We put, I put them on here and ride them.

And, and they have a sixth sense for horses and they would ride in the Nottoms with the local boys. And the thing is that you know, and like the, and the muggles, they would look like, you know, who are these little, you know, white upstart kids here, you know? And they, it was, it was tough and hard. And as a mother, you just close your eyes cause they’re like at full gallop and this is like uphills, downhills, like, you know.

They fall off, they, they, they can be dead. I mean, it’s really not, it’s really terrifying, but Genghis Khan created this to like create a man and, you know, you find your he more, as they call it, which is like wind horse. So it’s different in the Tibetan and then the Mongolian we say lungta, right in Tibetan.

So it means you’re good luck. You’re young. But there, it also means like your decisiveness, your direction, your ability to make decisions. You know, Genghis [01:03:00] Khan had strong -. And so a horse can give you that. So they were trying to create warriors, but what that gave my boys, I, is something it’s in the body.

It’s, it’s a bodily wisdom because, you know, they’re going at full speed on these horses and they have to trust. Yeah. And they have to build that trust. And it’s like, that’s why the horse is a metaphor for the mind and always has been in Tibetan Buddhism and why Dharma is carried on a horse. And the horse is a, we can learn a lot from horses.

And I’m really grateful to what Mongolia gave my, my boys, the horses gave my boys and growing up in, in, Kathmandu is, is really rich, but I will be very clear and honest with you. It’s very funny. I would take my boys up on pilgrimage up into Tibet. You know, we went around to a lot of main sacred sites of central [01:04:00] Tibet.

And my boys would be like, mom, no more monastery. We just want to play soccer, football. I think that, you know, but then it’s kind of beautiful cause now they’re in their twenties and if somebody asks them, they’re sort of, I think they kind of are just the way Mongols or, you know, high Himalayan people, they’re, you’re like, you know, what religion are you say?

I’m Buddhist. And you’re like, what do you know about Buddhists? You know, so they, I think there’s yeah, there’s still a little more of study and practice that can be done there. Yeah.

Olivia: But the foundation is there. It’s in their roots. It’s in their blood. Yeah.

Carroll: Yeah.

Olivia: They have good heart. Yeah, so for you raising them in that environment, it sounds like naturally they would be raised that way, because that’s where you and your husband wanted to be.

But even just beyond that practicality, what was it you wanted most for them to glean from being raised in that way, like moving between [01:05:00] these different cultures? for

Carroll: asking that. That’s a, it’s a beautiful question. I’m, you know, the, the ability. To love humanity and people in all their forms and all their ways to be at ease.

and see the humor and the joy of the diversity of life. So Nepal, I mean, oh my gosh, you know, the, the rituals like when you live in Nepal there’s a festival for every different ethnic community is celebrating. One of our favorites is Ma Puja, which is just so close to my heart, at least, which is usually practiced in the fall time around Tihar or Festival of Lights, Diwali, they call in India. But the Newars have Mahapuja and [01:06:00] you roll up the carpets and you create mandalas out of whatever harvest you’ve had that year. And we always made it our own family way, the way Thanksgiving’s everyone has different ones. And we go to see our, visit our Newar friends. We have beautiful ones with them, but then at our home, we kind of jazz it and we take all, you know, sight, sound, smell, and we play drum that we create. You say things you never would say you bless and honor each person in the family, and you always start with mama first, the origin of all things.

So the family. Together with that harvest and the light, the inner light, as it’s going just as fall is going to turn into winter. It’s something very deep and very profound. And then you sweep it all the way you put the carpet back. It’s your own secret private family ritual of bond [01:07:00] and linking together.

So powerful, so beautiful. And the Newars, no one is more. I mean, more brilliance on the life rite cycles and life rite rituals. I performed Burro Junkos for my mom here and my son had his paasni in New Jersey. The, the, the relatives are still talking about it. And so a posse is the rice feeding, but basically you honor them as divine their last before they become human, you welcome them as humans.

And then at the end you have – for your elders as they first turned 77 years, seven months, seven days. And all the way there’s about four or five, six of them. very elaborate rituals, very profound. It’s a lot better than getting a gold watch. The festivals and the rituals switch is really about that community bonding.

But I will say, you know, there’s other things too, you know, [01:08:00] Nepal. Has had a very tumultuous last 20 years. So there was also Maoist revolution. My children would go to school. There would be sandbags with people with machine guns out in front. You know, they, they’ve also seen really difficult and painful things.

And you know, we survived all the earthquake together. They they went out to help in communities and in villages. They also saw, they saw some nasty things, horrible things. Yeah, you can see, as we all know in Nepal, you can see things that with your raw naked eyes out the streets are, you know, I always used to say that Kathmandu is my university, you can get a PhD just in living, just by living in Kathmandu.

Very rich, rich, complex place and extraordinary, extraordinary beings. Yeah.

Olivia: Yeah. Yeah. And I love that you bring up to the rites of passage and even what you’re sharing right now, the rites of passage of just daily existence [01:09:00] there. Yeah. Seeing everything.

Carroll: And where ritual is just a part of everyday, everyday life.

That link, you know, I mean, you can imagine as a child and you’re, you’re, you’re raised with Cucurpuja every year, you just love it, right? You, you, you can’t shake those things.

Olivia: I have this one taxi driver when I go visit Kathmandu who I call up when I need a ride. And last time I saw him, I offered him a banana.

He’s like, I can’t eat bananas for another six months until this puja happens. And I was like, Oh, he’s like, but I love bananas. It’s just like, when does that happen? Right. He’s yeah. Cause he’s grieving his father’s passing and he can’t have any sweets until the cycle turns.

Carroll: A little bit of connection so deep?

Olivia: So sweet though, the holding of each other’s lineages in that way, like that there’s a way to work with the passing of time you don’t have to pre think, okay, how am I, am I going to process the passing of a parent? [01:10:00] This is what you do, right? Like, this is what you don’t do. It’s such a gift to have that.

Carroll: Oh, I think it’s one of the best places on the planet to die actually. Yeah. Yeah. Absolutely know what to do. It’s also a great place to give birth as I was, as I was trying to say actually too, because we, you know, women are treated so nicely. And, you know, you have a – 49 days just to bond with your child and they give you special foods and special massages and oh, it’s, Yeah, they know how to,

Olivia: that’s good to hear.

So I thought we could talk, we could move a little bit into some of your, I mean, we’re, we’re talking about a little bit already, but more of your anthropological work. And just starting first, I think today kind of the theme seems to be relationship. When you’re researching a topic, That is found in a community or a family or a person.

I imagine many times you don’t have a personal connection ahead [01:11:00] of time. In some places, perhaps you’re not there for a long time. And I’m wondering what you’ve learned in terms of creating relationship and reciprocity and safety for those you’re learning from, you know, so that you have this kind of ability to share.

Carroll: I so appreciate that. It’s so simple. It goes back, like, this is what I love when we, we go back to our core roots of Buddhist ethics. And we think of even you know, the six paramitas and we think of patience and kindness and, if we can listen, if we can approach with an open heart, people will, will respond to that. And we have to respect, you know, what, people want to talk about, people don’t want to talk about, and it’s different in different cultures.

I mean, how many times have you heard in Nepal where, somebody’s like, how much money do you make? And you’re [01:12:00] kind of like, Excuse me, you know, like for us, that’s not a polite question, just like I have to gently remind in Mongolia, you don’t say, how many animals do you have classic first American question, but you know, that’s sort of like saying how much money is in your bank account. There’s a guy named Paul Rabinow used to say comprehension of the self through detour of the other. If you’ve ever had your pulse taken with Amchi Sherab, any or anyone who’s ever had a pulse taken by a traditional healer, you know, it’s a deep listening and you feel seen.

You feel recognized. You are sometimes almost uncomfortable because you feel recognized because someone is just sitting quietly in deep silence but paying attention and so it’s really about coming with good intention, open heart, and an ability with deep listening, being ready to deep listen. So I have found in Nepal [01:13:00] often you know, there’s especially a lot of elderly women who just don’t feel heard, don’t feel listened to.

So they they feel grateful to have questions asked to them. They’re happy to talk . Now, I have also done work, you know, in brothels and with commercial sex trafficking where the worst thing I could do is to speak Nepalese because that was the language they spoke as kids.

Before a lot of trauma happened. So I’m just like re triggering them with trauma. So you have to be exquisitely astute and emotionally intelligent and also with timing. I love when you think about anthropology and questions, it’s like, what is going to be your first question?

What are your middle questions? And what are your last questions? And what is just going to be spontaneous? You know this better than anybody. You are asking questions all the time. And so how do we warm people up to feel [01:14:00] comfortable? And then where can we maybe put in a few difficult questions or things?

Or do we feel like we’ve created enough bond or presence where we can ask hard questions? And then how do we complete our session so that we feel like that bond is still there? And we’re complete in some way, or that this can be, this conversation can be reopened again.

I think it’s just like touching into our deep humanity. There’s no magical secrets. It’s really about taking a breath and being deeply present.

Olivia: Yeah, I really appreciate that answer. I think that piece you also say about the cultural delicacies, and I guess maybe what I hear too, is just the humility of that. Like you make mistakes, you learn what’s like totally not okay. Because you’re

Carroll: made mistakes, ,

Olivia: because I mean, you’re speaking to people about some [01:15:00] pretty intimate matters. That’s why I was very curious, you know, speaking of brothels or sex trafficking or yeah, polyandry that we spoke about earlier.

This is like intimate matters, like literally the most intimate parts of someone’s life. So yeah, I really value hearing that, that kind of like feeling in and just being in the process as two humans connecting.

Carroll: Yeah, because it’s just like how you phrased your question, which is the truth is really is you, you have to connect and you have to create relationship for there to be a genuine flow of information.

And, and there is a way where anthropology can be, I I’ve had many people who are just like, They have loved being able to share their stories and it’s been very healing, even sometimes very painful and difficult. Now I’ll give you examples like, you know, during the Maoist revolution, I had a good friend, anthropologist, and you know, she’s going down in Nepal gunge and so [01:16:00] working with human rights and now I need to write up my report.

So, and how many times were you raped and what happened? And it’s like, You are just re triggering and her realizing like it’s so horrible and it’s also with, the economic impact because it’s like, they get back in their white big Jeep, and then they drive away and people going, , All I have is this, and you want to rip this away from me too?

We saw the disaster vultures and the earthquake, and they come in, and you know, there, you know, there’s press that can come in, and they just want the story. Our son was devastated by that, and I said, stop. Stop, you don’t need to do this, you speak the language, put down your cameras, go, go into Bhaktapur and just sit with, just ask people, do they need help?

Just do that. And then if they want to tell you their story, they need to tell you the story, then you can say, I can help you to tell your story, but you don’t need, you [01:17:00] know, to go in there because sometimes when people are just like, Hey, I’m on assignment, I’m going to get this story and get in and out.

And you know, that’s, that’s not about creating relationship.

Olivia: Yeah. And I mean, it’s, it’s great hearing that from you because you have worked for quite official organizations, like BBC or National Geographic. So it’s so wonderful to know the level of integrity too, of how you enter into an environment.

Carroll: Oh yeah, I mean, I could tell you, like, I was working with this one BBC presenter and oh my gosh, this woman, she was of Polish origin. So when we went into the most radical Maoist youth environment group, and of course, and dangerous at that time, they were. They were responsible for some of the greatest violence that was happening in the country at the time.

And on the wall, of course, is, is Lenin, and Mao, and [01:18:00] Stalin, and Prachanda. And she goes, it just triggered her, and she goes, Can you give me one good thing that Mr. Stalin there did? We go to see the army general who had been exploded by a bomb, the Maoists there, so he was in a wheelchair, paralyzed.

And she, Gets him all angry and riled up. Then we go to see the royal astrologist. She gets him riled up. And I just was like going, you know, this is easy for you because you leave and get on a plane. I live here. I live here. I had to make sure I Made a safe way to get to my house, you know, it was dangerous, after talking with the youth group at that time period, and then having to work with these other folks.

So repairing relationships, restoring relationships. So, yeah, it really depends, you know, what you’re want and where you are. I used to [01:19:00] say to my husband, like during the Maoist time, it’d probably be better if you really want to go deep in the Maoist story, we need to not live here.

You can’t while we’re here, when you have family, can’t do it,

Olivia: it’s too dangerous. Did you, did you not do the Maoist story then at that point?

Carroll: Yeah, not, I mean, he, he saw things that he can’t unsee. He, he was there after some very major conflicts and saw really horrible things.

Yeah.

Olivia: Yeah.

Carroll: It was a rough, it was a really rough conflict. Yeah. Yeah.

Olivia: Yeah, yeah, I can

Carroll: realize.

Olivia: Yeah, definitely. I Yeah, it’s so interesting just hearing like as I’m like kind of feeling through the some of the different things you shared in the like that that non dual space experience that you’ve lived so clearly because your work has put you there at the front lines and your passion to be connected to people and sharing their story and your enjoyment of connecting with people.

It, it just feels, I feel the risk of it all. The aliveness of it.

Carroll: Yeah. Yeah. , [01:20:00] yeah. There’s, yeah, you, you, you have to be. That’s when I sort of met a little about when, remember when His Holiness the Dalai Lama said, not everybody’s your teacher. Yeah.

Olivia: I was like, you’re gonna, you’re gonna have to be careful.

Like he’s like, I see the future for you and you’re going to meet a lot of people. Yeah. Yeah.

Yeah. It’s like a whole tangent cause I’m so curious about well, obviously the pollution rates and agriculture there.

You live there. I think when there are still farmlands or even around Bodhinath stupa.

Carroll: Oh, yeah.

I mean, I always joke those of us that studied Buddhism that came from the West and came to Nepal to study Buddhism at that time were all the folks that flunked Impermanence and Buddhism 101 past lives.

So we were here to watch this [01:21:00] extraordinarily rapid rates of change. Unbelievable. And to, you know, and I mean, to bear witness to the Environmental devastation of the Kathmandu Valley is very exquisitely painful to bear witness to that. I would not lie to you. Yeah,

Olivia: do you see a pathway forward?

Carroll: Don’t underestimate the beauty and the brilliance of the Nepalese by any means. You know, it’s challenging. I take folks that go from Nepal to Bhutan and then they, and they don’t understand Nepal.

And I go, you know, well first of all, let’s just look at the demographics. You know, let’s go with the triangles. In India the triangle is like this with a lot of the so called untouchables on the bottoms in terms of just ethnic demographics, according to Hindu caste descriptions.

Nepal, what is like this, too many chiefs, not enough Indians. [01:22:00] Why? You know, the Mughals came down into India. And so then you had the Hindus. Migrating up, you know, I mean, some were there earlier, but most of the large majority a big blob and who were they was mostly the Kashyap Priyas, the warrior castes and the Hindus and the Brahmin and the Brahmin castes.

Those are the ruling castes of. Nepal government. So what you have is a lot of chiefs and not a lot of not a lot of Indians, so to speak, right? So that we don’t have a large, the large numbers of so called untouchable caste, et cetera. And I, you know, we can go into, you know, the, the debilitation of that, and from a governmental level, like I think it was fascinating watching the earthquake happen.

And for the first time, Globally, it’s like, well, what are you guys going to do? And Nepal government’s like, you know, we lose villages every year with monsoon, with landslides. We just went from feudalism not that long ago. And you’re asking us to respond like, like a services, like I will [01:23:00] do services for other ethnic groups and other people there.

No, no, we’re here to collect taxes. Like we’re not here to actually provide services. So, you know, you’re starting to see, like, look at those demonstrations, how for the roads and Boudha, et cetera, things like, you know, with water, Malimchi there, things are happening. Actually, there’s some really interesting things happening.

And we know the tragedies, huge, massive brain drain of, the best and brightest, well educated that have left. And there are some folks that are coming back and are trying to say, what are we going to do? Honestly, I go for all my medical health care in Nepal. I don’t do it here. I have so much more respect confidence and, and in terms of even dental care, the level, you know, the sophistication of the machinery that they’re using and their education levels.

So I think that, you know Nepal is a very complex place. It’s a lot easier in a place like Bhutan where they have, you know, the ethnic diversity is much, much less, you know, It’s a lot more complex than it is in a [01:24:00] place like Nepal.

So with that ethnic diversity and with its history coming out of feudalism, you know, it’s complicated. You have that density in such a small teeny area. So yeah, it’s challenging.

Olivia: Yeah. So let’s just speak on longevity. In the modern world

we certainly hear about this focus on how can we live longer? How can we be more youthful? Like how can the health of our mind, our sexual vitality, which we might elaborate on in a future conversation in general life force and lifespan. There’s a huge market for this right now.

Yet this isn’t a new area of interest for humans, this has been around also for a long time .

Carroll: It’s such a profound and a complex issue. I mean, yeah, look, you go from Silicon Valley where right now they’re putting big money into all this. Cause you know, we’re obviously getting an aging population even here in the U S we look at demographics globally, actually we’re, we’re getting less people, which is a lot of us [01:25:00] think is really fantastic economically for people who love capitalism and only have a growth model. Longevity is quality and the quality of our longevity and quality of long living. And obviously rasayanas In the Hindu tradition, chulen in the Tibetan tradition there’s a lot of texts.